Chapter 3

Tribal law and disorder

The Navajo Nation is one of 574 federally recognized tribes in the United States and, by most accounts, its justice system is one of the most sophisticated in Indian Country.

But a recent report by the Navajo Nation Police Department said current staffing levels were “dangerously low.” The report came out shortly before Ozzy Watchman and his daughter went missing in June.

The first time Watchman took his daughter, in December 2020, the police never responded to the family’s call for help, relatives said. Alice Watchman, the girl’s legal guardian, said she waited for police, but they never arrived. Navajo police said they did send out officers and make a report. Alice Watchman said she resorted to hunting for the missing girl using tracks in the dirt and snow. Ultimately, the girl returned home but had to be sent to a behavioral health clinic, she said.

When she called police after the June incident, Watchman said it took them three hours to arrive. Though the Navajo Nation stretches across four states, the Watchman farm is about a 15-minute drive from the police department in Window Rock, the seat of government.

The Navajo Nation doesn’t have a 911 emergency hotline the same way major cities do. To get tribal law enforcement to respond to an emergency requires knowing at least one of the multiple 10-digit numbers that connect to the local district’s police department.

“Even if you know that number, you’re not sure if they’re going to come,” said Amber Kanazbah Crotty, a council delegate for seven chapters of the Navajo Nation, a position akin to a U.S. senator.

Crotty, herself a sexual assault survivor, chairs the Navajo council’s Sexual Assault Prevention Subcommittee, which was established in 2016 after the abduction, rape and murder of Ashlynne Mike, an 11-year-old girl from Crotty’s district. Mike’s father filed a lawsuit against the Navajo Nation blaming his daughter’s death on delays in issuing an Amber Alert.

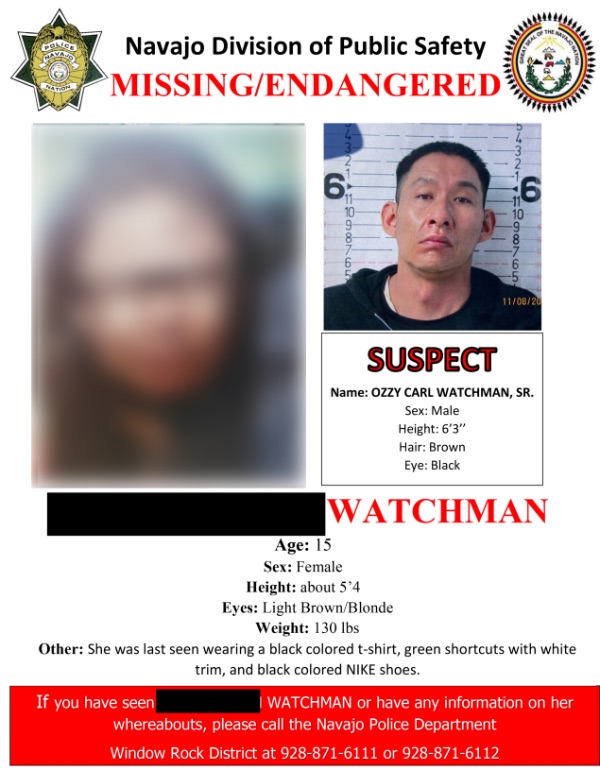

Navajo officials never issued an Amber Alert in June after Watchman took his daughter from her home, even though she is a minor and he is a convicted sex offender and not the girl’s legal guardian.

Phillip Francisco, chief of the Navajo Nation Police Department, said the incident didn’t merit an Amber Alert because “there was no reason to believe she was in imminent danger or serious bodily harm.” He said it was an “ongoing issue” and that the daughter “voluntarily left with the father.” Nonetheless, the department put a “missing/endangered” notice on its Facebook page a day after the two went missing.

Francisco said he was never told anything about allegations that Watchman had sexually abused his daughter, but he was aware of an earlier assault case involving the girl’s mother, Alberta Billie.

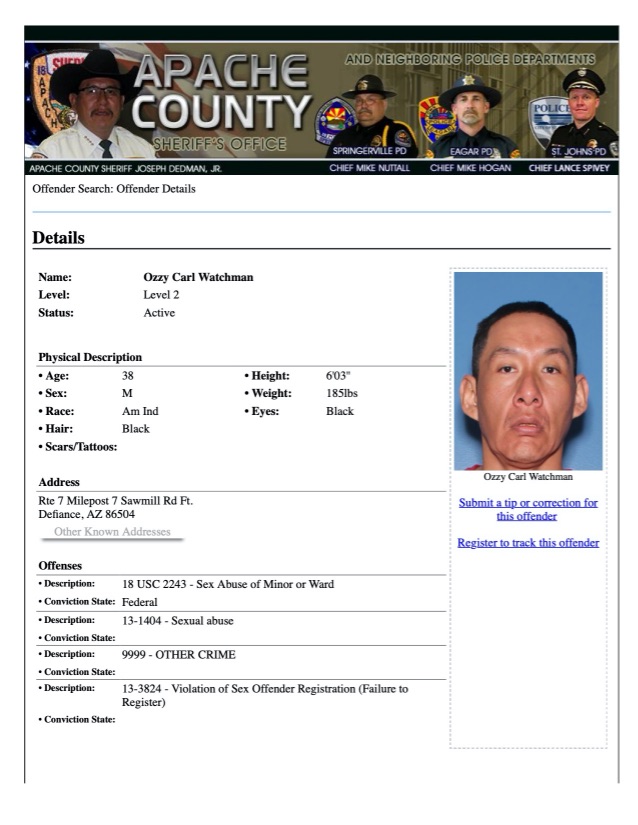

Watchman was convicted in 2006 of sexually assaulting a minor and in 2013 of assault on a minor for stabbing his son. In February, court records show, he brutally beat the mother of his three children. After he was found with his daughter in late June, federal authorities indicted Watchman for that assault on Billie. A spokeswoman for the U.S. Attorney’s Office in Phoenix would not say if prosecutors planned also to charge him with child sexual assault involving his daughter.

Both the girl’s guardian and mother said they were told an Amber Alert could not be issued because the girl, at 15, was too old. Francisco said the girl met the age requirement for Amber Alerts of 17 or younger but not the threat assessment. The girl’s mother also said she appealed to the FBI for an Amber Alert, but was directed back to Navajo police. The FBI does have the power to ask states in which a kidnapping occurs to issue an Amber Alert on behalf of a tribe, the former agent said.

“In my opinion they met the criteria for an Amber Alert,” said Crotty. But, she added, what happened in the Watchman case is a symptom of bigger, more systemic problems.

“My job is to figure out, are they (crime victims) being silenced because of lack of resources. Like, is law enforcement saying, well, we don’t have enough officers to go out there, so we’re not going to take this report?” she said. “And that’s what we were finding out, like dispatchers would kind of prioritize where officers would, what type of cases that they would go to.”

Crotty, who also sits on the government’s Budget and Finance Committee, says that in the Navajo Nation, resources for tribal police are nowhere near what’s needed to meet even basic law enforcement needs.

An independent assessment of the Navajo police department echoed those concerns. It not only found that current staffing levels were “dangerously low” but that officers were overworked due to understaffing. As of October 2020, the report said, there were 158 patrol officers to cover 27,000 square miles and 173,000 residents. To meet the current public safety needs of the Navajo Nation, the report said there should be 775 personnel, including patrol officers and command and support staff. Since that number could overextend the nation’s budget, the recommended personnel number now stands at 500. Other problems noted in the report include no internet or cellphone service in parts of the Navajo Nation, which has few real addresses.

“If you ask community members, do they feel safe in their communities? A large amount will say no because there’s still a lot of these challenges,” Crotty said, adding that her constituents feel “invisible.”

“I don’t understand why I don’t have running water. I don’t understand why it takes three hours for a police officer to come. I don’t understand, like, why a lot of these things happen,” Crotty said, summarizing their concerns. “And so I think congressional leadership doesn’t have any type of accountability to what’s happening here.”

Tribes are very limited in their taxing abilities; for example, they can’t levy property taxes. Additional funding for tribal law enforcement is supposed to come from the federal government. But federal funding for law and order in Indian Country is allocated by two departments with differing expertise — the Justice Department, which handles law enforcement and judicial functions, and the Interior Department, which has historically handled matters in Indian Country.

The Justice Department cannot provide base funding to tribal courts or tribal law enforcement because that authority belongs to Interior’s Bureau of Indian Affairs. Justice can offer grants, but that varies by administration. In addition, the grants are competitive, often short term and complicated for tribes to apply for and administer.

One of the recommendations of a 2013 Tribal Law and Order Act commission was to restructure and simplify Indian Country public safety funding, giving the Justice Department the authority to provide permanent base funding and eliminating the grant-based system.

“You have a federal Major Crimes Act, a federal law, so you need to properly fund that,” Crotty said. “You know, your system created this, and so we can go only to a certain point.”

Ozzy Watchman Sr. mentioned wanting to spend Father’s Day fishing at Wheatfields Lake, which is on the Navajo Nation near the Arizona-New Mexico border, said his uncle, Leonard Watchman. When he disappeared with his daughter on the Friday before Father’s Day, Leonard Watchman told his sister to call the police and later told authorities about the Wheatfields remark. But no one seemed to listen, he said.

In the end, that’s exactly where the two were found after being spotted by the maintenance worker, about 30 miles away from Alice Watchman’s farm.

The girl spent three days, including her 16th birthday, in the hospital. After the December incident, she’d told a relative that her father had sex with her several times, the family member said. Authorities were notified of this, but nothing happened as a result.

“The sex offender was taking the girl and seems like nobody cares,” said Alice Watchman.

Previous Chapter

Previous Chapter