When Purdue introduced OxyContin, sales representatives and promotional ads said that less than 1 percent of people would ever become addicted to OxyContin, according to a 2009 article by Dr. Art Van Zee, an internist certified in addiction medicine.

“They were falsely promoting opioids as safe and effective for conditions where opioids are not safe or effective,” said Dr. Andrew Kolodny, executive director of Physicians for Responsible Opioid Prescribing, a national advocacy group for proper prescribing methods.

The medical community began encouraging doctors to alleviate their patients’ pain and introduced the pain assessment scale and patient satisfaction surveys. It became understood that compassionate doctors took care of their patients' pain, fast. In other words, they prescribed painkillers.

The surveys ask, “Was your pain handled adequately?” Doctors who do not receive satisfactory results from the surveys are often reprimanded or can even lose their jobs, Berman said.

Doctors have said they often do not receive adequate training on how to deal with chronic pain, and the training they do receive is often sponsored by pharmaceutical companies.

That aspect hasn’t changed much.

“In many ways, that education is still dominated and influenced by the pharmaceutical industry,” Kolodny said. “Most of the education is still pretty bad.”

But since the 1990s, Kolodny said the medical community has grown more skeptical of industry influence and has turned to other ways of learning about new drugs.

“You read medical journals not sponsored by the pharmaceutical companies,” Berman said.

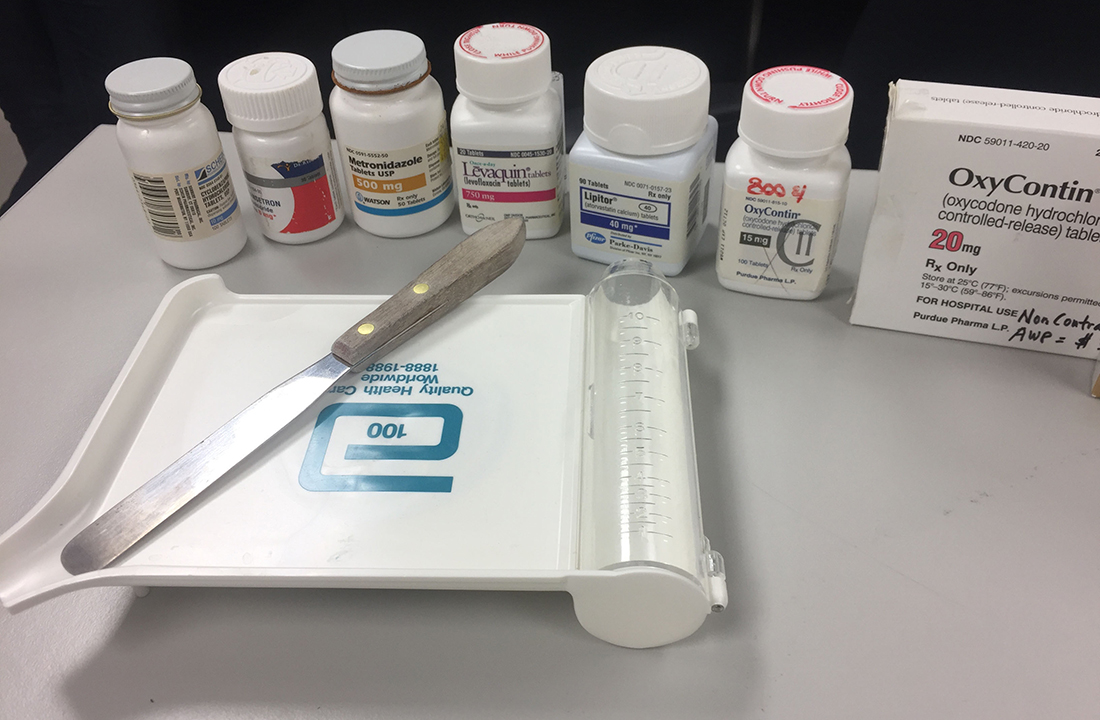

As more people became addicted to opioids and overdose deaths skyrocketed, authorities began cracking down on some of these companies.

In 2007, 27 attorneys general settled a multi-million dollar lawsuit with Purdue for illegal and deceptive marketing tactics and for misbranding their product. “We made our mistakes in the past and accept responsibility for that,” said Bob Josephson, a spokesman for Purdue Pharma.

Although several Valley doctors said they don’t see the same aggressive marketing tactics popular decades ago, the industry still pushes hard.

Johnston, the family practice doctor in Glendale, said sales representatives continue to stop by the office.

“There’s pressure from pharmaceutical companies all the time on doctors,” Johnston said. “They’re always trying to knock on your door and talk to you about the latest and greatest.”

Kolodny said the companies have new ways to incentivize doctors to keep writing prescriptions for their products.

“It’s not like they’re paying you to write a prescription,” Kolodny said. “They might say to a doctor, ‘We want you to give a dinner talk for some of your colleagues at this really nice restaurant so you can talk about your experience treating these conditions because you’re such an amazing doctor.’”

Kolodny called the accusations against Insys, the Chandler-based company, unique.

“They literally bribed their doctors to prescribe their drug,” he said. “That’s usually not the way it works with pharmaceutical companies.”

In a news release, Illinois Attorney General Lisa Madigan said the state's case against illustrates Insys’ disregard patients’ health: “It’s this type of reprehensible and illegal conduct that feeds the dangerous opioid epidemic and is another low for the pharmaceutical industry.”

The Arizona company, which distributes its products nationwide, had a team of about 75 full-time research and development personnel and 343 full-time marketing and sales employees. It spent nearly $2 million in legal fees in 2013. Two years later, legal fees jumped to just under $19.5 million, according to financial records.

From 2014 to 2015, net revenue increased $122.8 million, or 124 percent.

“They just want to make the money,” Berman said. “This is a company. This is a business. This is not about caring about people. This is about a bottom line.”

However, Malone said it’s not uncommon to see a few companies make huge strides in revenue if they manufacture a novel drug.

“It’s probably a function of meeting an unmet need,” he said. “There was obviously huge demand for the product, and it made an impact in patients’ lives.”

.jpg)

CONNECT WITH US

Connect with our reporters and editors through social media, or call or email an editor from our contacts page.

Sign up for daily headlines