Federal aid divides homeless in the Twin Cities

The Twin Cities of St. Paul and Minneapolis have faced an alarming rise in homelessness during the pandemic, but there’s nothing similar in how they’ve confronted the crisis.

By Helen Wieffering, Agya K. Aning and Helena WegnerHoward Center for Investigative Journalism

ST. PAUL, Minnesota — In two rooms in separate cities, people say their names. Around a circle of chairs and tables, they gather weekly to strategize leaving the streets behind. All have been homeless before or are living on the brink.

The conversation is more urgent, as a pandemic winter sets in. And frustration is building with public leaders who they feel have not done enough to help.

The Twin Cities of Minneapolis and St. Paul, though similar in many ways, have taken opposite approaches to tapping the largest homeless aid package in American history.

Congress included $4 billion for emergency homeless aid in its pandemic relief bill last spring. Officials in Minneapolis and surrounding Hennepin County moved quickly to use the $17.5 million granted them under the Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security Act. But St. Paul and surrounding Ramsey County officials have yet to touch the nearly $8 million in homeless funding they were allocated. As of early December, they had not even finalized plans for how the money would be used.

Of the 362 communities eligible for the homeless funding, many share an urban footprint, connected by bridges, bus routes or highways. San Francisco and Oakland, Tampa and St. Petersburg, and Dallas and Fort Worth all received the emergency grants, scaled to the size of their homeless populations. But no other set of twin cities has as big a gap in funds or planning as Minneapolis and St. Paul.

At an early November virtual meeting, Junail Freeman Anderson pressed a Ramsey County commissioner to work harder to house St. Paul’s homeless. As she spoke, some 300 people were living unsheltered in the city.

“We’re no joke,” said Anderson, 45, who has been homeless more than 10 times. “We need help. And we need it now.”

Anderson represents Freedom from the Streets, a group she founded in St. Paul in 2019. Together with Street Voices of Change based in Minneapolis, the two organizations offer a platform for the thousands of people living in tents and shelters throughout the Twin Cities, which are confronting an alarming rise in both homelessness and cases of COVID-19.

Unsheltered homelessness has soared in recent years. The number of people living on the streets or in cars, parks or skyways was 980 at last count, almost five times higher than in 2015, driven largely by a lack of affordable housing. The closure of public spaces and reduction of shelter beds to allow for social distancing in the pandemic have deepened the crisis.

When Congress passed the CARES Act in March, it used the Department of Housing and Urban Development’s annual homeless grant program to funnel about 14 times the previous year’s annual amount of aid to local communities to prevent and prepare for the spread of the coronavirus among the nation’s nearly 600,000 homeless people.

Local governments were required to submit spending plans and HUD approval to access the funds. By early December, nearly 90% of them had received at least some aid, according to an analysis of federal data by the Howard Center for Investigative Journalism.

But not St. Paul.

“It should be considered a state of emergency,” said Tyra Thomas, a member of Street Voices of Change who was homeless off and on for two decades. “Where’s all this billions of dollars, you know, that the state got?”

Well before the pandemic, Thomas saw homelessness in the Twin Cities building to a crisis. “All bets are off,” she told the Howard Center. “Let’s just get ’em inside.”

The bigger, richer twin

If Minneapolis and St. Paul are twin cities, then Minneapolis is the larger and wealthier sibling.

The city’s spending power is more than twice that of St. Paul’s, and its affluent suburbs bring in extra tax earnings for county leaders. While the two cities have similar homeless rates, Minneapolis’ larger homeless population earned it more federal homeless aid. And unlike St. Paul, Minneapolis benefitted from HUD consulting help, starting in March, on the best ways to use the pandemic dollars.

By July, Minneapolis and Hennepin County officials had allocated most of their emergency homeless funding toward expanding the number of shelter beds and homeless services. They also used shorter-term, general coronavirus relief aid on shelters and hotels, where vulnerable homeless residents had been moved in the spring.

Minneapolis had been planning to expand shelters even before the pandemic. David Hewitt, director of the Hennepin County Office to End Homelessness, said that allowed the city and county to move swiftly when the federal funding was released. He said they felt a “sense of urgency” because they knew that opening shelters can take longer than expected.

“We wanted to get the money out the door,” Hewitt said. “We are into a COVID winter now, and we don't quite know what that's going to bring.”

City and county officials, who jointly direct the aid, devoted almost half of their homeless grant, or $7.7 million, to address stark racial disparities among their homeless population. The American Indian Community Development Corporation received $300,000 to nearly double the size of its outreach team on Minneapolis streets, and another $1.8 million went to operate a new shelter for Native Americans.

HUD has encouraged aid recipients to use funds in racially equitable ways because of the racial disparities in both homelessness and the impact of COVID-19. Black and Indigenous people make up less than 15% of the Twin Cities’ population but account for 65% of all homeless people. Black and Indigenous Minnesotans have also died from the coronavirus at disproportionately high rates, according to state health officials.

By late November, daily coronavirus infections were setting records in Minnesota, with about 450 total cases among the homeless.

Part of the homeless aid awarded to Minneapolis will help expand outreach among the city’s outdoor encampments. One of the largest lies along the Midtown Greenway, a busy bike path cutting west through the city. David Jeffries visits daily along with the rest of his outreach team at Avivo, a nonprofit serving people facing poverty, addiction and homelessness.

Officials granted Avivo $200,000 to hire additional outreach workers. Jeffries said homelessness had worsened during the pandemic and estimated 200 to 300 people are still living unsheltered in Minneapolis.

“This is just a fraction of what's really here,” he said, gesturing at the multicolored tents along the Greenway. “It’s bad, and it has not slowed down.”

Even with greater resources in Minneapolis, problems persist.

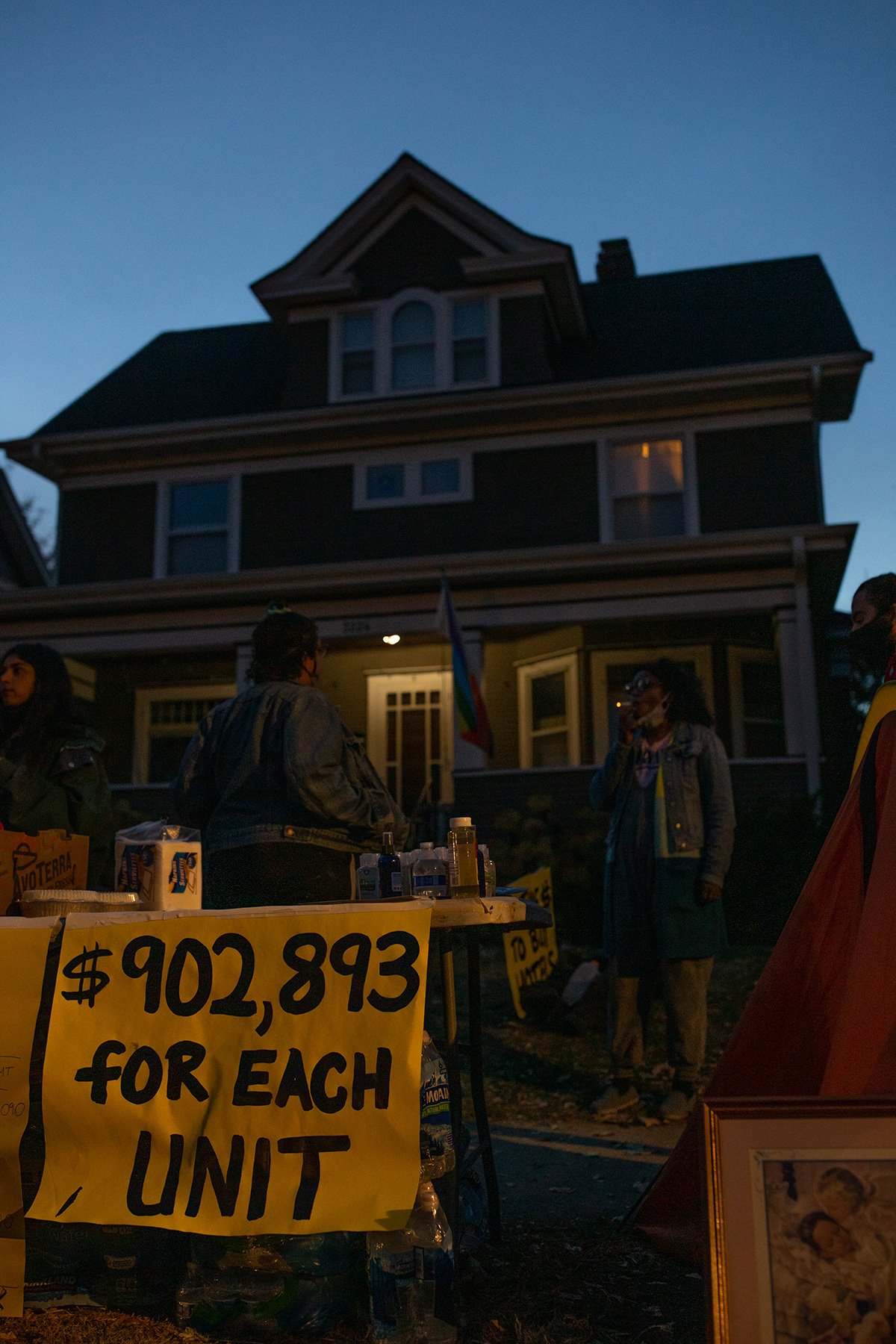

The Friday after Election Day, roughly a dozen activists stalked the sidewalk in front of a Hennepin County commissioner’s home. They covered a table with posters and handouts, and on a thin strip of grass, they pitched two tents.

The group was protesting the county’s reversal of plans to purchase a hotel in the southern suburb of Bloomington to house the homeless. At the time, the hotel was already occupied by dozens of people with no other place to live. Shelters for single adults in Minneapolis were at capacity about 10 days later.

The city and county also faced an uphill battle with another shelter investment.

Over the summer, officials reserved $5.6 million of the federal homeless aid for a north Minneapolis shelter for women of color. Street Voices of Change supported the project, which Thomas said was desperately needed so that women wouldn’t have to shelter alongside their abusers.

But neighbors strongly opposed the project; some pushed for a youth center while others worried it would bring crime to the area. Ultimately, Hewitt said, Minneapolis Public Schools scrapped plans to donate a vacant school building for the shelter. A space in south Minneapolis is expected to open for the winter while the search for a permanent site continues.

Unsheltered in St. Paul

When the pandemic hit, the number of homeless encampments across the Twin Cities exploded. As many as 700 tents overtook Minneapolis parks in July. But by late fall, the numbers declined after the city stopped permitting encampments and moved some people to shelters and hotels.

In St. Paul, an estimated 300 people remained outside in scattered enclaves, their numbers rising tenfold since before the pandemic. “Just month over month, we had a hundred more people outdoors,” Deputy Mayor Jaime Tincher said.

By the end of October, which saw heavy snowfall, there wasn’t anywhere to put them; St. Paul shelters quickly filled to capacity.

The number of people sleeping outside in St. Paul was partly why Anderson and the rest of the Freedom from the Streets group gathered for the Nov. 6 video call to demand action from county officials, who share control over the federal homeless aid.

Ramsey County Commissioner Trista MatasCastillo said she was feeling frustrated, too. She told the group that the county would be purchasing sleeping bags, coats and winter boots for people living outside.

“We keep working within the constraints that we have to work in,” the commissioner said, adding that state officials had declined requests for help in finding more shelter.

“There is now, quite literally nothing else we can do on our own in time,” the county said in an Oct. 27 letter to the Minnesota division of Homeland Security and Emergency Management. “Without immediate State assistance we will likely experience more deaths as winter grows and know for certain that the health and safety of these unsheltered residents is at serious risk.”

It was the second time Ramsey County officials had asked the state to find and operate new shelter space. In the months since their first request in May, the number of those living outside in St. Paul had doubled to more than 300, according to city officials.

“A lot of them will die if they stay outside,” MatasCastillo told the Howard Center.

Eric Grumdahl, deputy director of the Minnesota Interagency Council on Homelessness, said in an interview that the state’s role was not to operate shelters, but rather to provide funding and technical assistance.

“The State will not be taking on the new role of standing up and operating new shelter capacity in response to your emergency request,” Grumdahl’s boss, Cathy ten Broeke, said in an Oct. 30 letter to Ramsey county officials.

County leaders were adamant they needed more than funding; they wanted the state to identify, design and operate shelters, and provide staffing, as well. “If today we got $100 million, we still couldn't solve this problem,” MatasCastillo told the Howard Center in November.

A few days before Thanksgiving, however, city officials announced they had received additional state funding and would open two new temporary overnight shelters for 100 homeless people. A week later, county officials announced an additional $2.4 million in state funding to continue housing about 300 of St. Paul’s unsheltered homeless residents in hotel rooms until the summer. They also said they had secured more winter shelter beds at a St. Paul seminary, in addition to those already planned for a former hospital near the state Capitol.

By Jan. 1, Ramsey County’s manager said, there would be enough shelter for everyone.

St. Paul and Ramsey County officials have said they did not tap their nearly $8 million in emergency homeless funds because they wanted to first use general coronavirus relief aid before it expired on Dec. 30. Staggering funds, they said, would allow them to extend homeless services farther into the future.

And yet the county repeatedly appealed to the state for aid and, prior to receiving the additional state funds, had said it would allow the hotel contracts for hundreds of people to expire at the end of the year because of a lack of funds. Cities elsewhere in the United States have used the emergency homeless funds for such expenses, the Howard Center found.

Max Holdhusen, Ramsey County’s planning chief of housing stability, said county employees were overwhelmed by the large federal grants.

“Every single service needs to have someone who plans it out, who communicates with the providers, who then drafts a contract, who approves that contract,” Holdhusen said. “I want to expand services, but it stretches our contract managers and our planners kind of to the brink of capacity.”

Steve Berg, vice president for programs and policy at the National Alliance to End Homelessness, said St. Paul wasn’t the only community holding emergency funding in reserve. The decision may make sense if overall funding is scarce, he said, but “it’s frustrating” if people are sleeping on the streets in communities awarded millions of dollars to address homelessness.

“There's money available that's sort of designed to be used to keep them safe and they're not getting around to it,” Berg said.

The pandemic arrived as Ramsey County was trying to reorganize and streamline a struggling homelessness response infrastructure. Members of Heading Home Ramsey, the organization responsible for coordinating homeless services and resources, said in interviews they were often constrained by a lack of funds and shifting policy mandates from HUD.

When a separate group of political leaders, foundations and outreach workers known as Outside In began gathering a few years ago, they were seen as more agile and effective. Angela Gauthier, associate director of a St. Paul nonprofit for Indigenous homeless youth, said it became clear the Heading Home Ramsey strategy lagged behind.

“We were kind of floundering,” she said.

The two homeless organizations plan to begin work in January as a single coalition after nearly two years of planning. Advocates hope it will help local leaders devise a homeless strategy better than the current one, which one homeless service provider likened to putting out fires.

When asked about criticism that Minnesota had not done enough to help, Grumdahl said in a Nov. 5 email that St. Paul and Ramsey County had received millions in state funds to address their homeless issues, as well as received $41 million in state-directed federal aid that could be used to help the unhoused.

Yet, in an earlier interview, he agreed more had to be done in the Twin Cities.

“The fact that we continue to have hundreds of Minnesotans who are tonight spending the night outside is a demonstration that we don't have enough of what we need," Grumdahl said.

Reporter Madeline Ackley contributed to this story.