Officials try to stop fake prescriptions, but addicts remain persistent

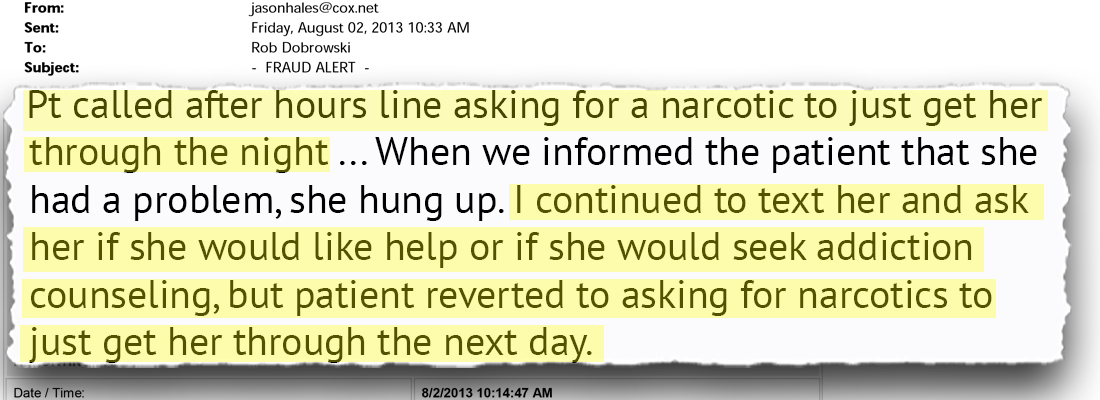

PHOENIX – In an unrelenting quest for painkillers, Arizona pill seekers embark on almost daily missions to obtain fake or stolen prescriptions and shop their pain among doctors. Sometimes, pharmacists report, patients try to get “multiple, multiple narcotic” prescriptions from “multiple, multiple doctors.”

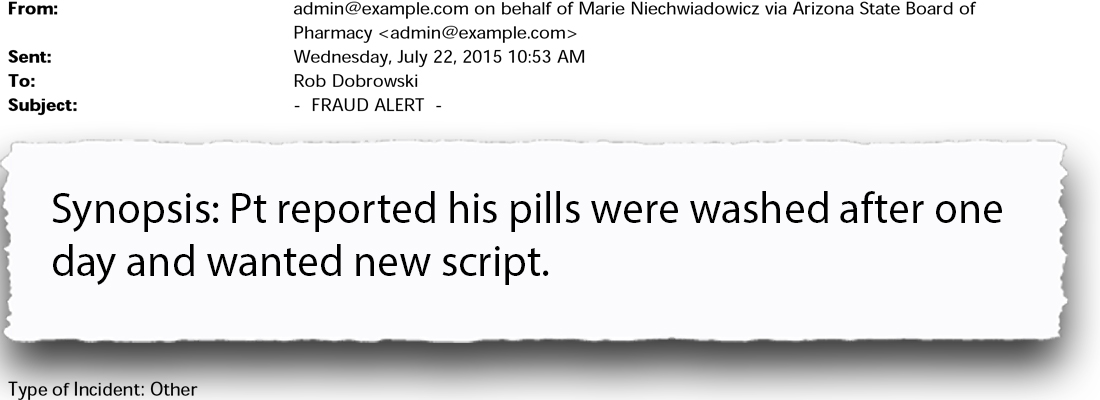

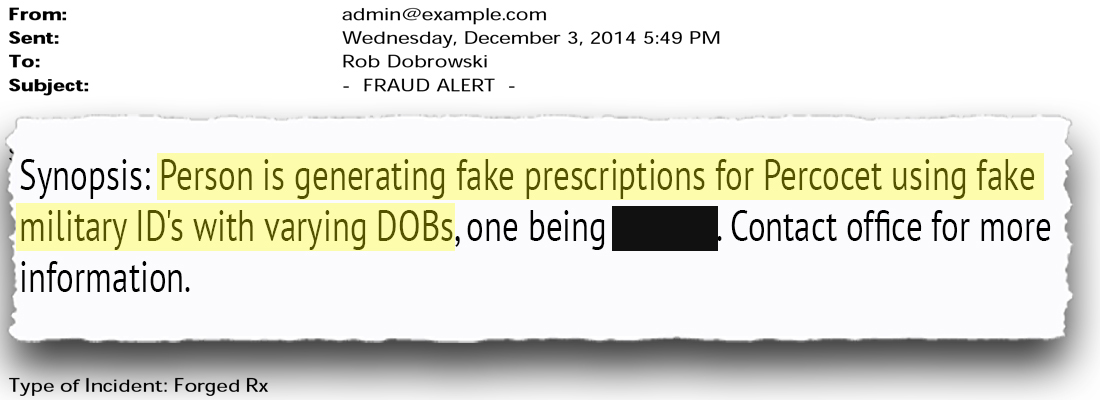

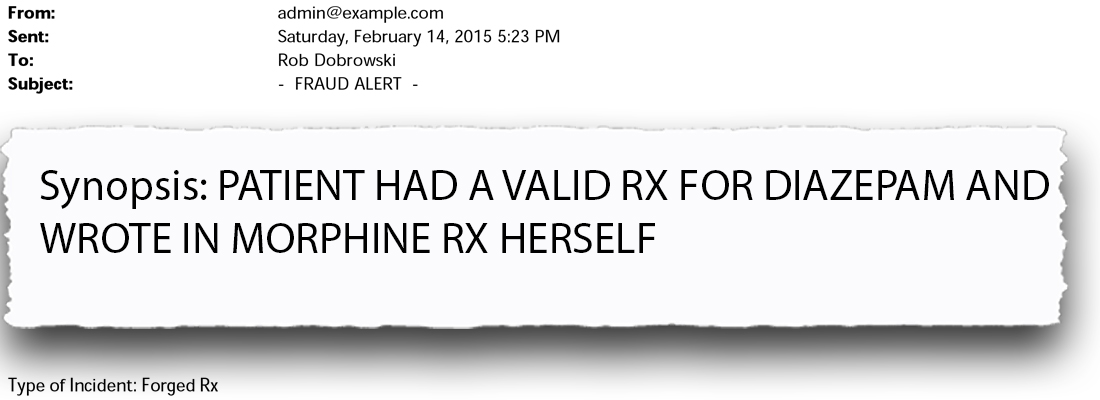

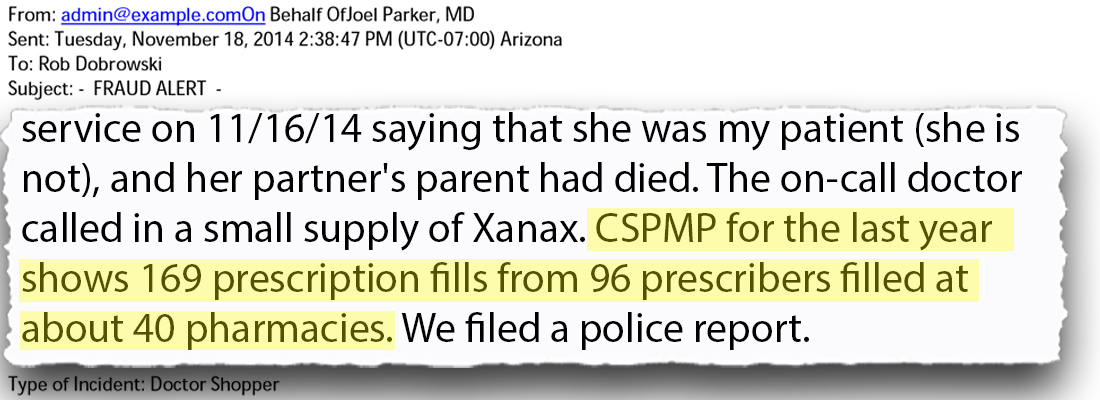

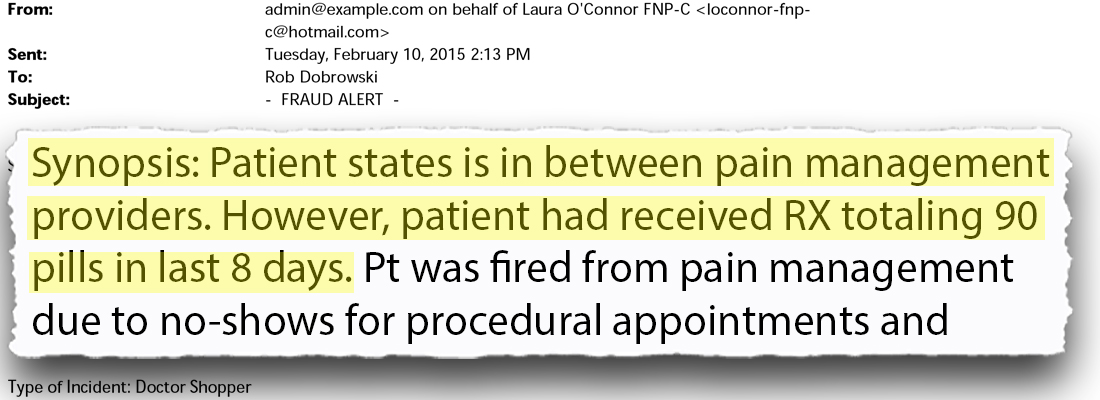

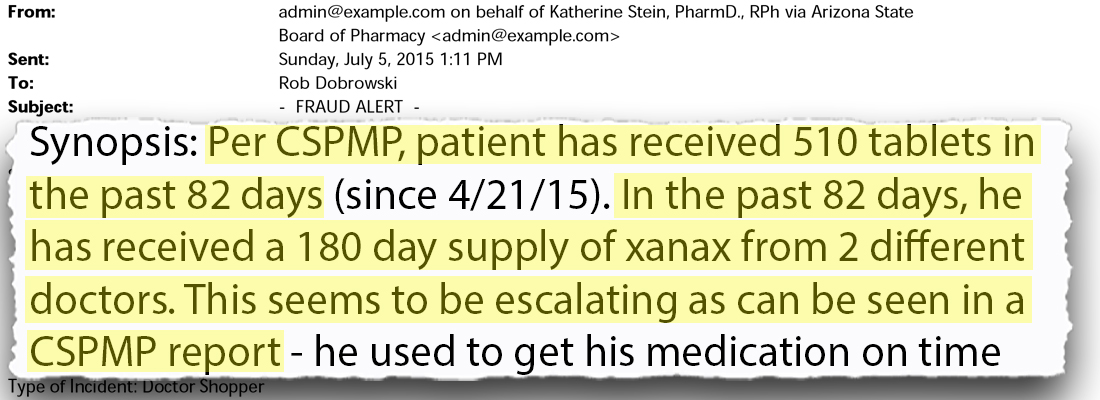

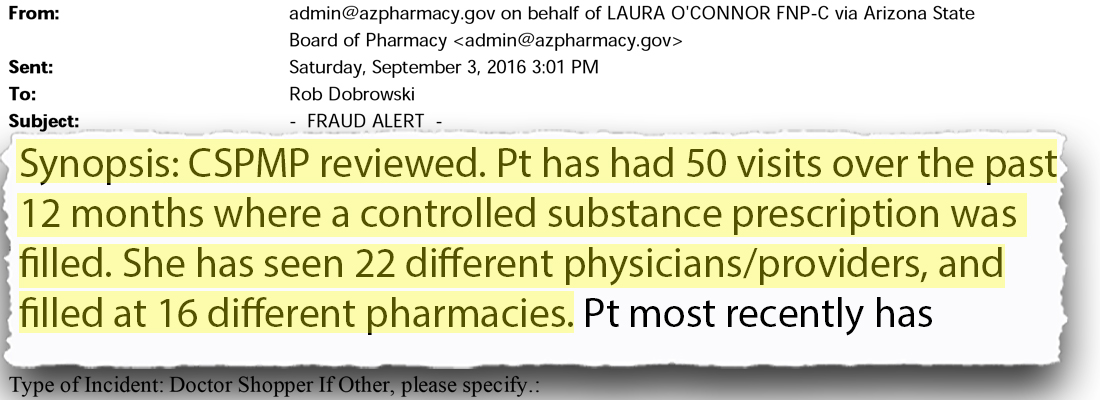

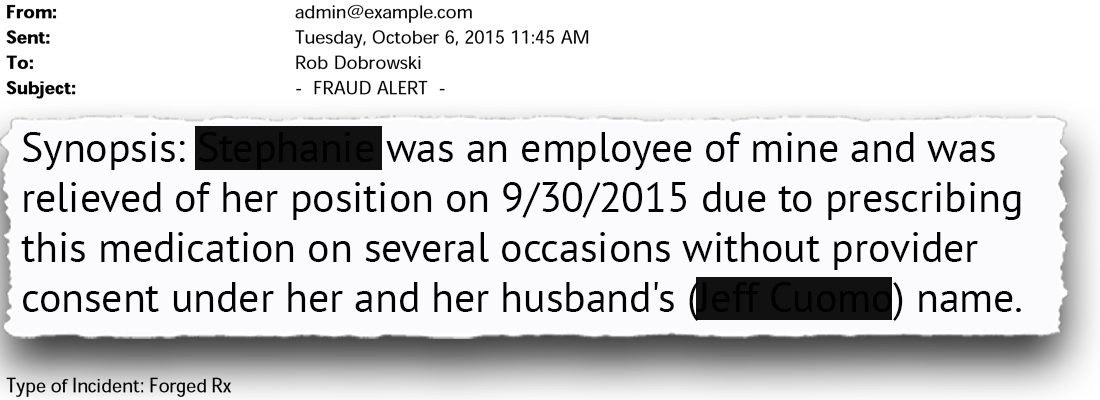

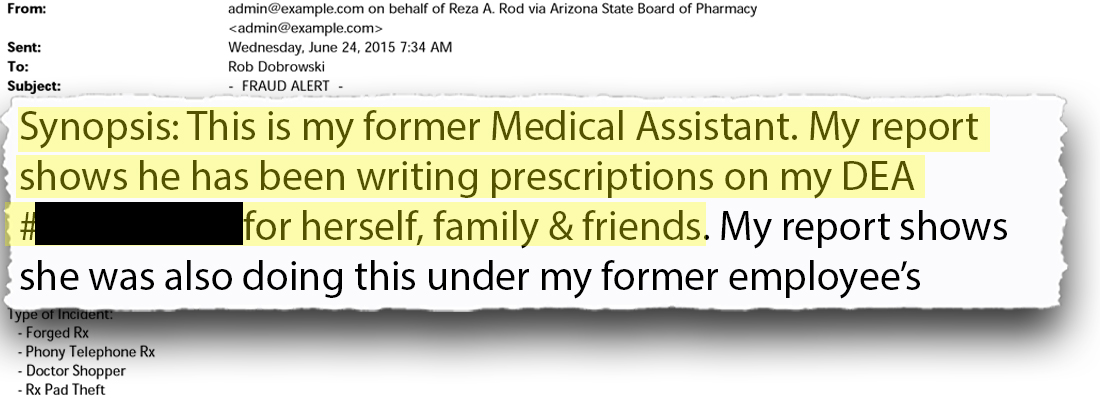

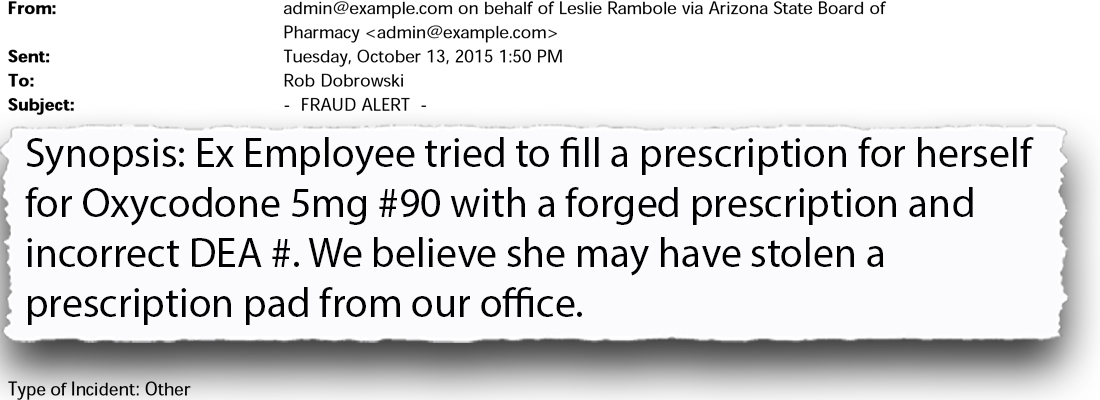

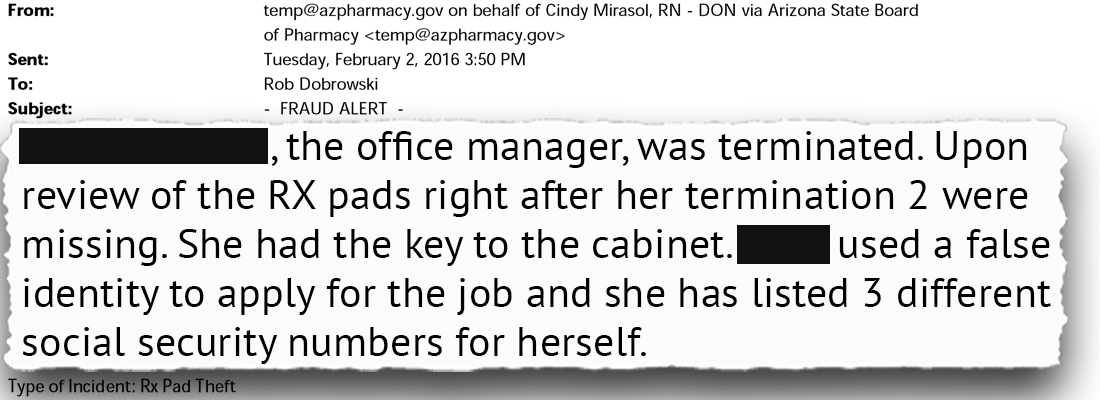

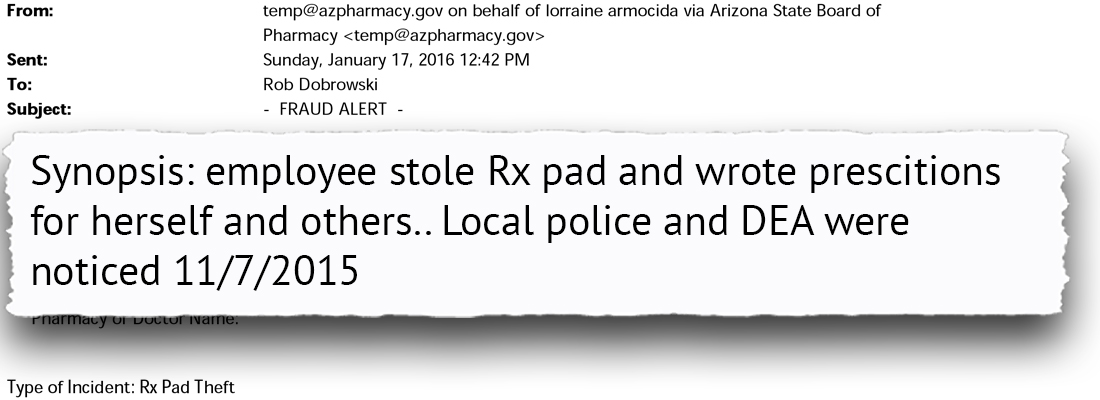

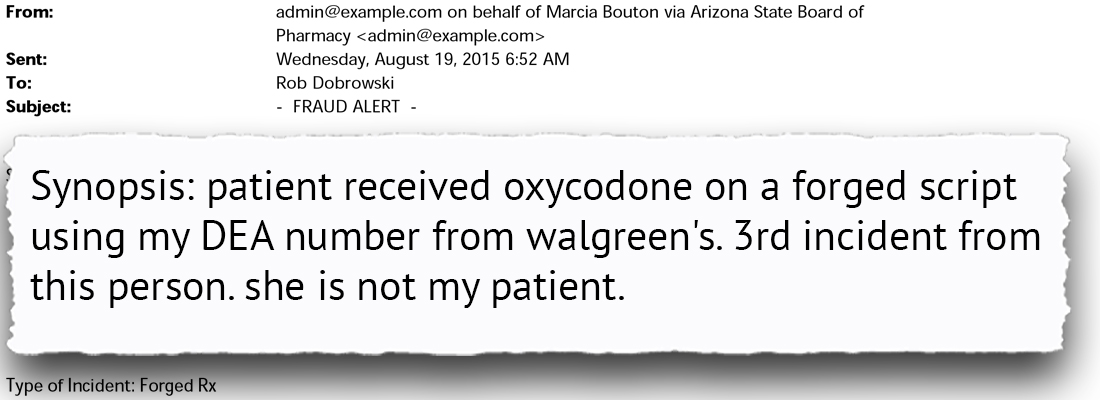

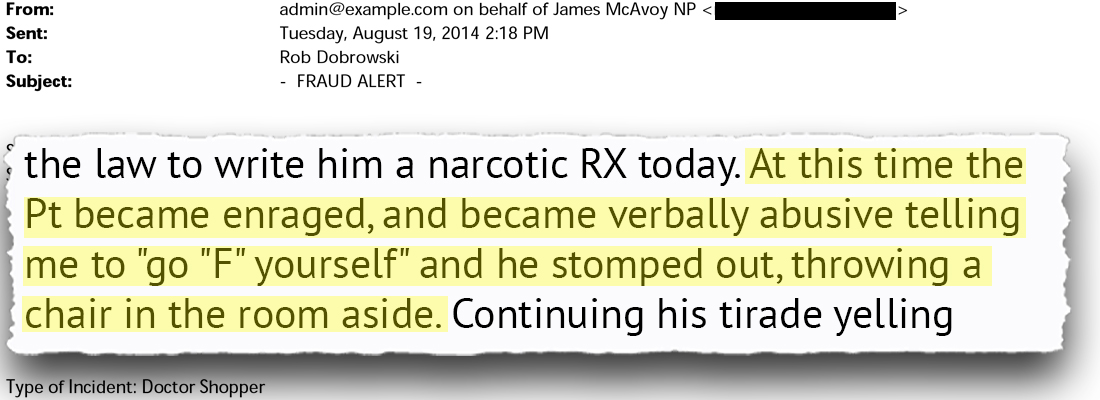

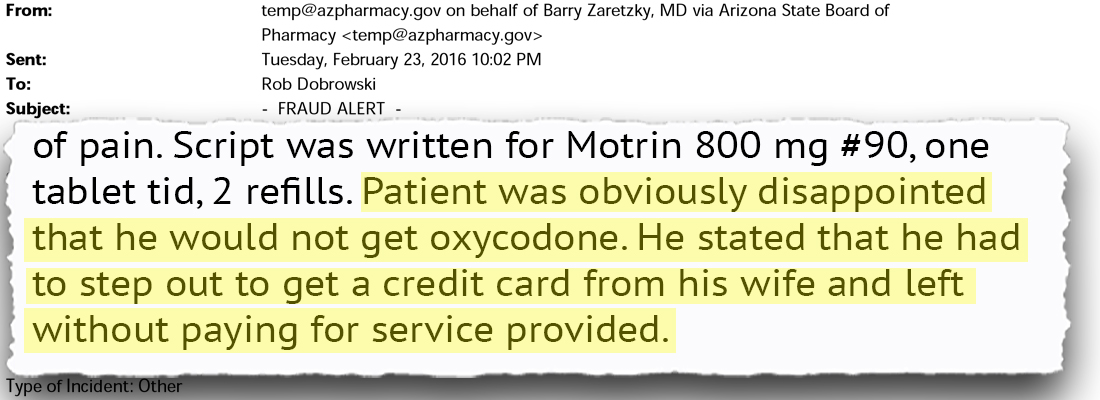

Though the Arizona State Board of Pharmacy and lawmakers have built ways to thwart prescription drug fraud, Arizona’s addicts and abusers are equally persistent. A Cronkite News review of of almost 800 “fraud alerts,” which are regularly sent to the board by concerned medical professionals and pharmacists, details the extent to which doctors and pharmacists are confronted with people willing to try almost anything to get painkillers.

According to one alert, a woman received 130 narcotic prescriptions from 93 prescribers, dispensed by 41 pharmacies. Another patient “has had 50 visits over the past 12 months where a controlled substance prescription was filled. She has seen 22 different physicians/providers, and filled at 16 different pharmacies.”

A Mesa pharmacist also reported a female patient bringing in a prescription for Promethazine with codeine in October, but after calling the woman’s doctor, it was determined that the “prescription was written on either a stolen prescription pad or was created by the suspect.”

Another alert, submitted by a dentist, describes a woman, brown hair, 5 feet 4 inches tall, claiming she needed Percocet because of a codeine allergy. According to the dentist, “patient appeared inebriated, incoherent at times, details of events changed with each telling. Came with a gentleman using a walker, both insistent that she be given Percocet, angry that I wouldn't provide it, left without paying.”

Cronkite News conducted a four-month investigation into the rise of prescription opioid abuse in Arizona. In 2015, more than 2 million grams of oxycodone alone came into the state, the third-highest total per capita in the country.

Dozens of journalists at Arizona State University examined thousands of records and traveled across the state to interview addicts, law enforcement, public officials and health care experts. The goal: uncover the root of the epidemic, explain the ramifications and provide solutions.

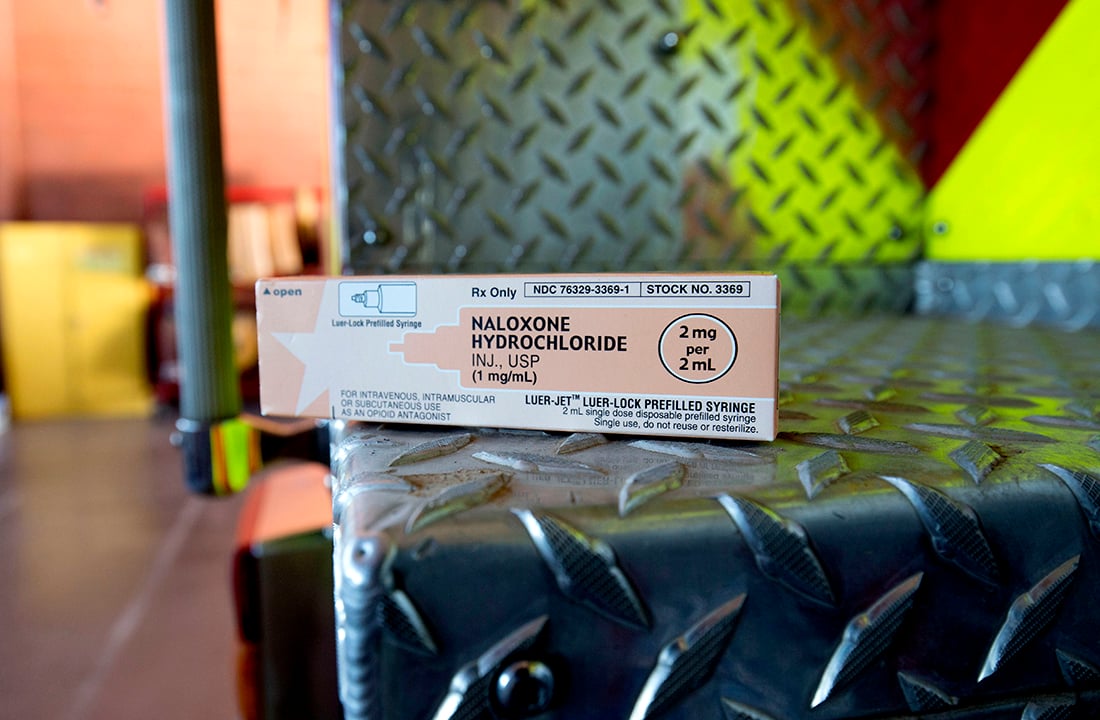

Since 2010, more than 3,600 people have overdosed and died from opioids in Arizona. In 2015, the dead numbered 701 – the highest of any year before, or nearly two per day, according to an analysis by the Arizona Department of Health Services.

The state launched the fraud alert system in 2013. Although the alerts often contains the name, address, physical description and sometimes the Social Security number of the potential drug seeker, no one – not the police, not the pharmacy board, not anyone – is responsible for further investigation.

“(Following up) is not part of our statutes, or our responsibility,” said the pharmacy board’s Executive Director Kam Gandhi. “We’re actually a conduit, we send off the information from what’s provided to us. We’re not the enforcer, (nor) generally follow up on it.”

Rob Dobrowski, the board’s information technologist, said the fraud alert system is just one way to provide “a public service to keep everyone informed on the ongoing fraudulent prescription activity.”

The board also runs the Controlled Substances Prescription Monitoring Program, or CSPMP, which is supposed to keep doctors and pharmacists accountable for the drugs they prescribe and keep addicts from getting them. When a patient comes into a pharmacy with a prescription, pharmacists log the drugs into the CSPMP. Doctors who use the system then can see what medications a patient already has received.

CONNECT WITH US

Connect with our reporters and editors through social media, or call or email an editor from our contacts page.

Sign up for daily headlines