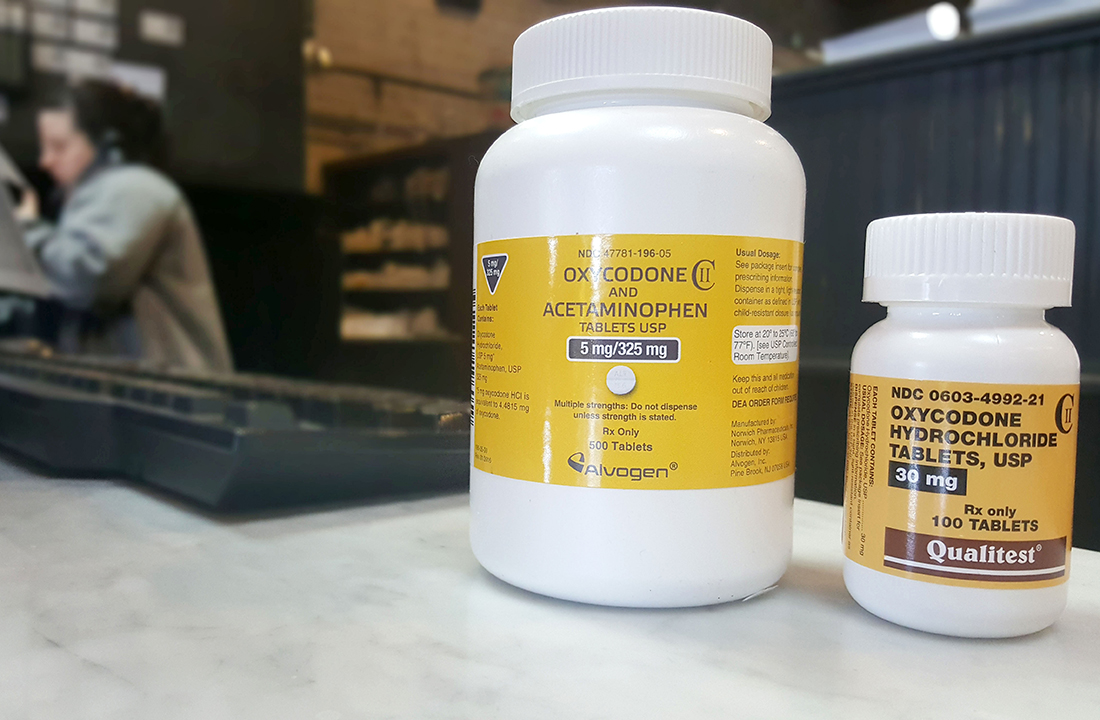

Opioid overdose deaths continue to mount each year

MESA – John Koch knows about dying. He said he’s flatlined three times. But with each overdose, paramedics and doctors brought him back.

“There’s no light when you die,” he said. “It was just darkness. … I’m an addict. Death didn’t scare me as long as I got my fix.”

When Koch was 14 years old, he found his opioid addiction first in Vicodin pills from a friend, then through fentanyl suckers.

“I loved it,” he said. “Shortly after that, I got introduced to OxyContins. From there, nothing was more important than getting my OxyContin, every day.”

At the time, he said 80 mg OxyContin pills cost between $60 to $80 each.

“I just did whatever was thrown my way,” he said. “I didn’t know what I was doing, but if it got me higher, I wanted to try it.”

His parents spent hundreds of dollars to put him into rehab. He said he went to jail at least 20 times. He moved on to heroin. Death didn’t scare him.

Since 2010, more than 3,600 people have overdosed and died from opioids in Arizona. In 2015, the dead numbered 701 – the highest of any year before, or nearly two per day, according to an analysis by the Arizona Department of Health Services.

“When you have more deaths from prescription drugs than car accidents, something is really, really wrong,” said Will Humble, division director for health policy and evaluation at the University of Arizona’s Center for Population Science and Discovery. “Over time, we continued to track that epidemic, and it kept getting worse. This opioid epidemic was getting worse every year.”

Humble said it’s going to take years for the opioid-prescription deaths toll to subside. He applauds Arizona Gov. Doug Ducey’s recent executive order that Arizona’s Health Care Cost Containment System limit initial opioid prescriptions to seven days.

Last year, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention reported that “the United States is experiencing an epidemic of drug overdose (poisoning) deaths. Since 2000, the rate of deaths from drug overdoses has increased 137 percent, including a 200 percent increase in the rate of overdose deaths involving opioids (opioid pain relievers and heroin).”

The CDC also reports that since 1999, the number of overdose deaths involving opioids nearly quadrupled, with at least 78 Americans dying every day from an opioid overdose.

“We now know that overdoses from prescription opioid pain relievers are a driving factor in the 15-year increase in opioid overdose deaths,” the CDC report says, adding that the number of prescription opioids sold in the U.S. nearly quadrupled since 1999. “Deaths from prescription opioids – drugs like oxycodone, hydrocodone, and methadone – have also quadrupled since 1999.”

CONNECT WITH US

Connect with our reporters and editors through social media, or call or email an editor from our contacts page.

Sign up for daily headlines