By Nicole Tyau / Cronkite Borderlands Project

Published July 11, 2016

SZEGED, Hungary — Four refugees — two women and two men — sit on an oak-colored bench on the left side of a courtroom 9 miles from Hungary’s border with Serbia. Three of them wear medical masks. Silver handcuffs and their tightly clasped hands tether the four together as they stand before the court.

They are flanked by two armed and stone-faced guards. The judge, Dr. Sàudor Moluàr, is seated at his perch overlooking the courtroom.

One by one, the refugees are unshackled to stand before the court with a translator. They listen as the judge reads from statements they made to police detailing their crimes: They all had crossed into Hungary illegally.

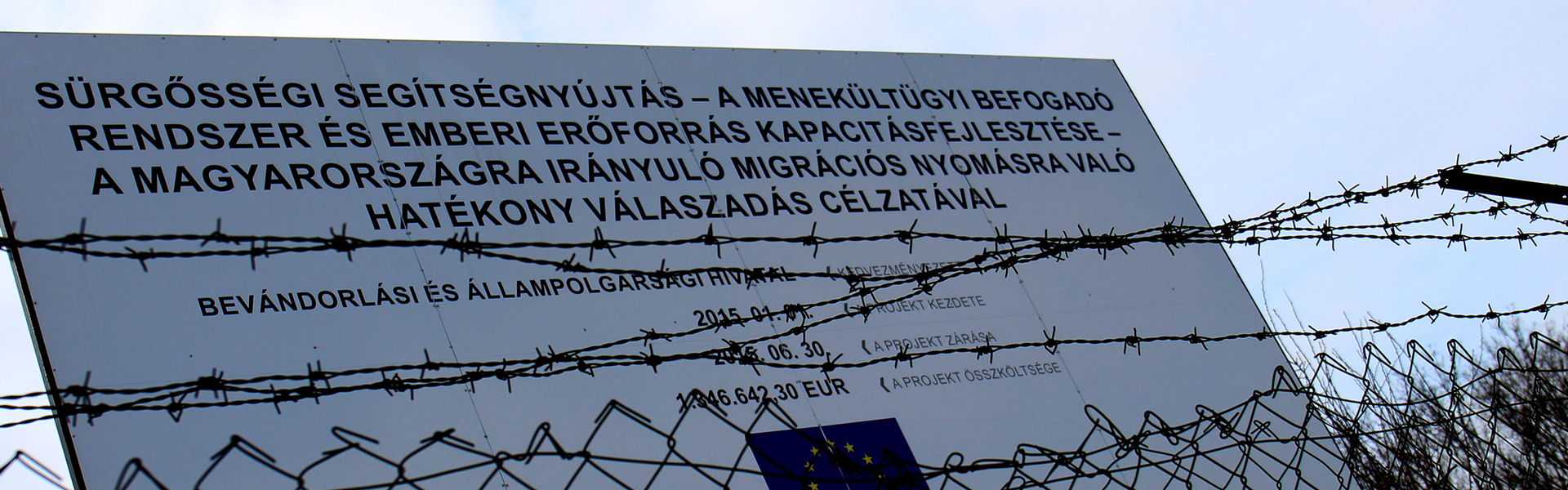

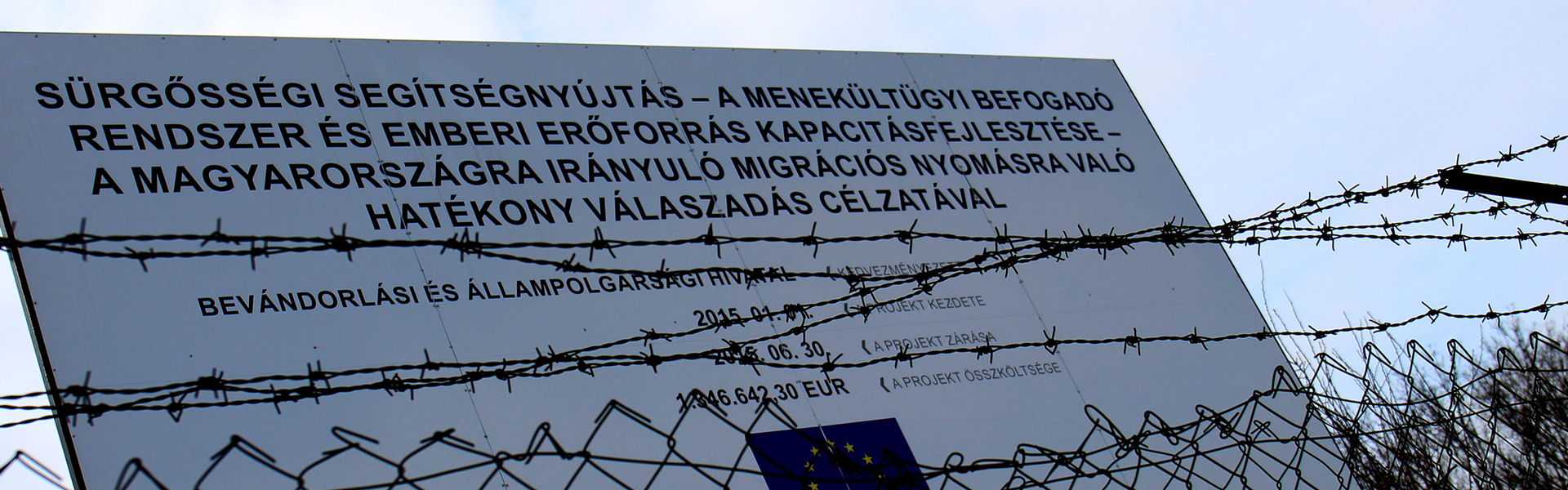

For migrants who have crossed illegally into Hungary since it erected its 109-mile border fence with Serbia in August 2015, an appearance in the yellow-walled courtroom in Szeged is the beginning of a legal odyssey. They cross into the country illegally, are tried swiftly and sentenced to deportation, but they may never leave because no one is sure where they should go.

Europe was not equipped to deal with the legalities of deportation when the migrant crisis exploded in April 2015, fueled largely by Muslim refugees fleeing the civil war in Syria. Conflicting regulations have created strife between countries including Hungary and Serbia, resulting in a gridlock that has left migrants in limbo.

Months after the refugee crisis began to overwhelm the continent in 2015, the European Union called for the enforcement of its so-called “Dublin Regulations.” According to these rules, the first EU member country the migrants enter must process their asylum requests. The country that processes asylum requests becomes the country where the refugees would potentially live.

Had the rules been enforced from the beginning, most of the refugees would have been processed in Greece or Italy, where the majority of refugees entered the EU. But according the EU’s Eurostat, few were processed in those countries. Hungary processed nearly seven times as many applications as Italy and Greece combined — a discrepancy that had no small impact on Hungary or the EU.

“Everybody stated that Dublin was dead. Dublin has collapsed. Dublin is defunct,” said Hungarian Justice Minister László Tróscányi, explaining the Hungarian position. “There are instruments of law that are enforced but are no longer applicable.”

Before the EU started enforcing the Dublin Regulations, Hungary would process asylum requests and send migrants northward to their preferred destinations. However, when the Dublin Regulations were enforced by the EU, countries were required to take back the migrants who had applied for asylum but left. Hungary’s Prime Minister Viktor Orbán flatly refused to abide by the EU’s decree.

The dispute left refugees such as Ali Reza Azimi, 35, and his family in limbo. Azimi, who is Iranian but was working in Afghanistan when his family left for Europe, paid smugglers in Athens to take them to Hungary. By bus, by train and mostly by foot, they traveled from Greece through Macedonia and Serbia and finally to the Hungarian border.

“As soon as we crossed, lights came on,” Azimi said in an interview in early March. “The police were there waiting for us.”

The family was sent to a detention center with no freedom to come or go. “Went to a closed camp,” Azimi said with a shrug. “No place for people.”

After the detainment, Azimi said his family was sent to Switzerland, the final destination they had hoped to reach. After living there for six months, Switzerland sent the family back to Hungary, citing the Dublin Regulations. Ever since, Azimi, his wife, and their children, Hamed, 4, and Hamid, 10, have been living in the refugee camp in Bicske, a small town about a half hour west of Budapest. Residents there are allowed to leave on day trips and return to camp by night.

A Tesco shopping center a 2-minute walk down a narrow road from the Bicske camp became a popular spot for refugees to spend some of the weekly allowances they receive from the Hungarian government. On this day, Azimi plays with 4-year-old Hamed in a small playground at the shopping center while conducting the interview.

While Azimi hopes that his family can return to Switzerland, they are trying to acclimate to Hungary. Azimi and his wife are taking Hungarian lessons, and their children are finally in school.

(On March 16, a representative from the Orban’s ruling Fidesz party announced that Hungary would be closing all refugee camps and replacing them with tent camps on the Austrian border.)

The Azimis’ case under the Dublin Regulations is different than those cases of migrants detained crossing the border illegally. But for all migrants, part of the decision on how they will be handled by Hungary’s courts lies with how they are classified.

According to Hungarian law, “refugees” are people being persecuted in their home countries and who would face immediate danger if they continued to live there. They can apply for asylum. “Economic migrants” are people “seeking a better life;” and “migrants” are people transiting the country under Europe’s open border policy. The last two categories would be more likely to be sentenced to deportation.

But adhering to the classifications has proven difficult.

“I believe that this distinction or these three categories -- it’s just impossible to put 1.2 million people into these three categories,” Trócsányi said. “What actually collapsed -- and this is why the European system collapsed -- [is] no country’s public administration can do this.”

Hungary has attempted to send refugees back to its southern neighbor Serbia, where it contends they should have registered and applied for asylum. But non-profit groups like the Hungarian Helsinki Committee say Serbia has blatantly anti-refugee laws and a broken asylum system that could never guarantee the refugees safety. Moreover, Serbia’s relations with Hungary have been strained ever since the border fence was erected and the country has significantly reduced the number of deportees that it has taken back, slowing the process.

“Justice administration is a system that is rather slow when it comes to changes,” Trócsányi said.

Trocsanyi said Hungary faced tough choices in dealing with the refugees. He said Hungary owed it to the EU to defend its southern border and to safeguard its own people and its internal security.

“The fence was a measure of last resort,” Trócsányi said.

With tens of thousands of refugees flooding into the country, the government and the people were overwhelmed, and, according to Trócsányi, so was the rest of Europe.

In Hungary, the legal system was unprepared for the number and speed of trials for illegal immigrants. Non-profit advocacy organizations have been providing free legal assistance to the refugees, but access to them has been difficult.

Andras Lederer, a legal specialist from the Hungarian Helsinki Committee, said they weren’t allowed to enter the “transit zones,” created on the Hungarian-Serbian border to receive incoming refugees, to talk to their clients. Instead, Lederer said that lawyers had to advise refugees through the chain link fence.

In a report, the Hungarian Helsinki Committee said the legal system has failed the refugees and that the country’s asylum system is faltering. It contends the courts have been unable to fairly adjudicate cases.

But Natasa Fulöp, secretary judge for Hungary’s National Judiciary, said trials for the illegal immigrants have been designed to move quickly for the migrants’ sake, with judges able to handle upwards of 100 cases daily.

“The migrants shouldn’t be in custody for longer periods,” she said, explaining that the court system extended hours to weekends, rented extra buildings, and reallocated resources to handle the load.

The trial in Szeged is an example of the process.

The four refugees were captured on March 8, 2016 — one day before the trial. They had fled Pakistan more than a year earlier.

When they scaled the razor-wire topped fence into Hungary there were 50-60 people of different nationalities crossing from Subotica, Serbia.

“It took about two hours to get to the border where there was a barbed wire fence,” the first defendant says in her testimony to police. “I knew it was Hungary on the other side of the fence.”

The defendant, a woman in her early 30s, stood before Judge Moluar making eye contact only with the translator, her head never moving from a bow.

“Do you know what you’re being accused of?”

She says she does.

“Do you understand the charge being levied against you?”

She says she does.

Moluar tells her she has her rights in the courtroom: to object, to not testify against herself, to change her mind about testifying. He tells her what she says can be used against her.

The judge reads her testimony to the police, and the three succeeding cases go almost identically. Within an hour, the evidence had been heard, each migrant had stood before the judge, and they had all made their statements.

The second defendant, a woman in her 20s asks the judge for leniency; she has a little girl. Another defendant has just turned 18, he says, but he has no proof of identification. He asks for leniency because of his age.

Judge Moluàr takes 15 minutes to deliberate before he brings the four migrants back into the courtroom. Because they are so young, and because they were smuggled into the country, he has decided to be lenient, he says, and he ordered them deported. They were given a two-year ban on re-entering Hungary.

After refugees have been sentenced and while they await deportation, they will taken to a closed camp, which they are not allowed to leave or an open camp that allows day trips, Fulop, the secretary judge said.

Many refugees go to the prison in Vác, just north of Budapest, which has a more than 160% overcrowding average. If they don’t go to prison, they will go to the two new open camps on the Austrian border, which have replaced the several other camps and reception centers throughout the country, including Bicske.

The Hungarian Helsinki Committee contends that the way Hungary’s legal system is dealing with refugees, many of whom are fleeing war, violates the 1951 Geneva Convention. The committee says refugees who cross a border illegally should be allowed to present themselves to authorities and demonstrate a good reason for transiting. But Hungarian officials counter that breaching the fence is the crime, not simply crossing the border, and that the convention rules therefore don’t apply.

“I think, and I can say it with lawyer’s responsibility, that whatever we have done, what we have done, legally, is in order,” Trócsányi said. “On the one hand, protecting your own borders with a fence is not forbidden in any of these. Whether it’s likeable or not, nice or not, it’s as they say a separate cup of tea.”

Buffett student projects include: Nicaragua: Channeling the Future | Chiapas: State of Revolution | Two Borders | Puerto Rico: Unsettled Territory | Stateless in the Dominican Republic | South Africa: At the Crossroads of Hate and Hope | South Africa Documentary | Borderlands Photo Essays | Divided Families (PDF) | Divided Families Documentary | Children of the Borderlands | South Africa Project

Cronkite News is the news division of Arizona PBS. The daily news products are produced by the Walter Cronkite School of Journalism and Mass Communication at Arizona State University.