By Cassie Ronda / Cronkite Borderlands Project

Published July 11, 2016

BUDAPEST, Hungary — Standing outside in the misting rain, Hungarian Prime Minister Viktor Orban praises the virtues of the “glorious Hungarian nation” to a large crowd of his compatriots.

“By nature, Hungarians stand up for what is right when the need arises,” says Orban, according to the official government translation. “What is more, they fight for it if needs be, but do not seek out trouble for its own sake.”

It is March 15th, 2016, a Hungarian national holiday commemorating the revolution of 1848. In video recordings of the event, Orban is seen speaking from an elevated stage in front of the wide steps and stately columns of the Hungarian National Museum.

“Our reputation travels far and wide; clever people and intelligent peoples acknowledge the Hungarians,” says Orban, who is in his sixth year as Hungary’s leader.

He delivers his speech in Hungarian, a language shared by fewer than 13 million people worldwide. He is flanked by Hungarian flags and wears a Hungarian tri-colored ribbon on his coat lapel.

But beyond the patriotic platitudes, Orban delivers a message to those who have criticized Hungary’s aggressive anti-refugee stance as xenophobic, anti-Muslim and racist.

“In Europe today, it is forbidden to speak the truth,” he says. “It is forbidden to say that the masses of people coming from different civilizations pose a threat to our way of life, our culture, our customs, and our Christian traditions.”

In reaching this point, he relives years of Hungarian history marked by foreign occupation, multiple revolutions, shrinking borders and oppressive governments. His audience knows it well.

“We shall not allow others to tell us whom we can let into our home and country, whom we will live alongside, and whom we will share our country with,” he says.

Orban communicates a belief that the migrant crisis threatens the culture Hungarians have historically fought to protect. He is charismatic, and he is the prime minister, but does he truly reflect what Hungarians feel? And what does it mean to be a Hungarian, anyway?

In the days before Orban’s address, we spoke with people in and around Budapest, and we found that Hungarian views on the refugees are inescapably colored by the nation’s past.

Fruzsina Folk says history is her favorite subject, but not Hungarian history.

“They always pick the wrong side!” says the 21-year-old, who lives in the suburbs of Budapest, “every war, the wrong side.”

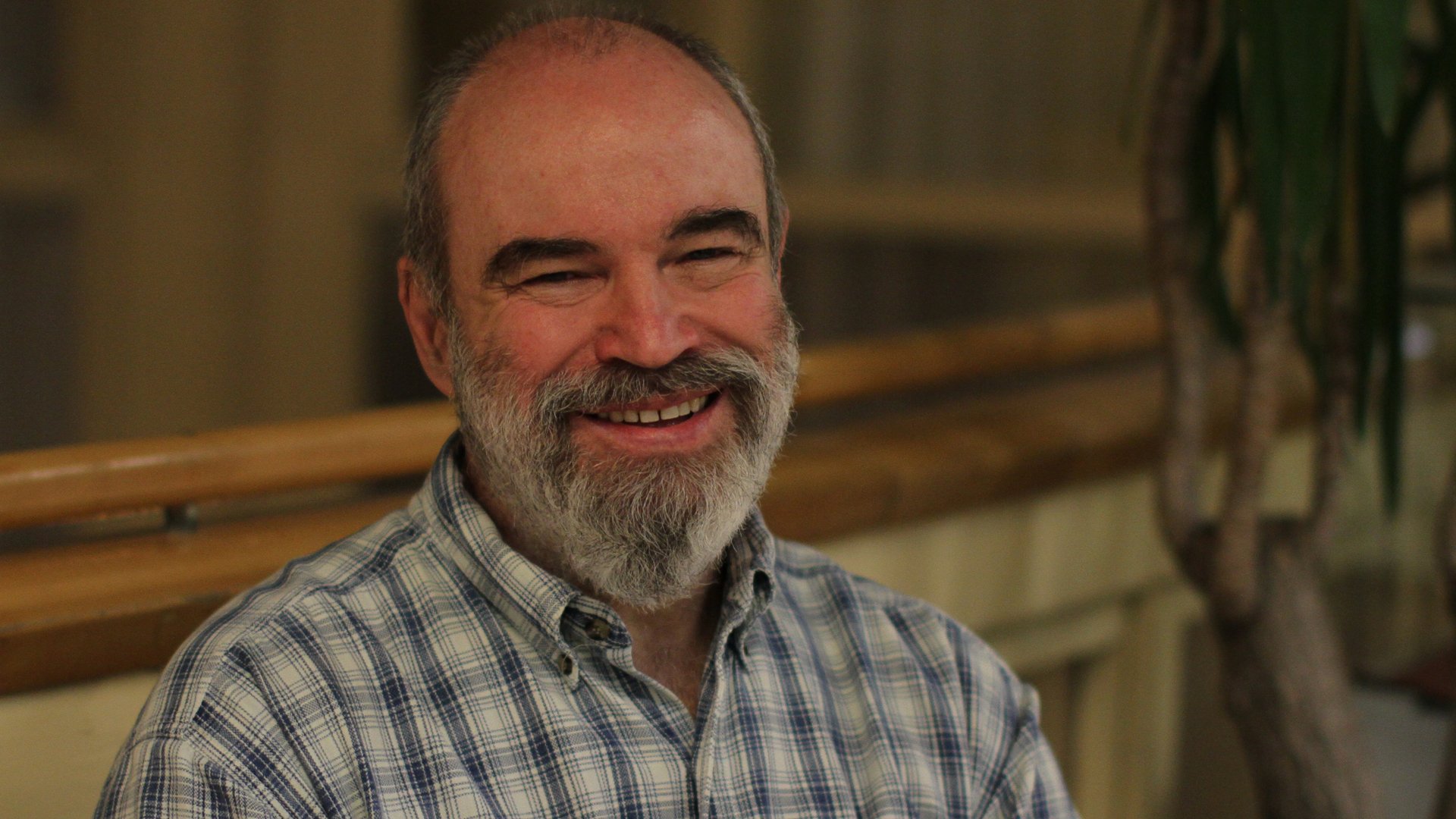

“That’s true,” says her father, Ivan Folk, a 56-year-old Protestant pastor and musician. The father and daughter share an easy rapport, switching from English to Hungarian whenever a question relates to a private joke or a mutual understanding.

Fruzsina’s frustration originated during an intensive Hungarian history course she took to finish her high school requirements. Her teacher covered a millennium of events in just three months. And those 1,000 years highlight a vicious cycle of Hungarian defeat.

In the 13th century, early Hungary was overrun by the Tatars. Then came ransack and rule by the Ottoman Turks from the mid-1500s to the early 1700s. Next, the Austrian Hapsburgs assumed power over the country. During that reign the Hungarians staged the much-heralded 1848 revolution, still celebrated on March 15th, but Austria regained control just two years later. The nation suffered catastrophic losses of life and land in World War I, and a subsequent alliance with Germany led to further defeat in World War II and decimation of most of it Jewish population. After that, Hungary was swallowed up by the Soviet Union. Another brave revolt, this time against communism, was crushed in 1956. In fact, 1991 marked the nation’s first attempt at democracy.

There were also some nice parts, Fruzsina concedes. But mainly she remembers how often the Hungarians disagreed among themselves.

“If there’s two Hungarians in one room, there’s like 12 different opinions,” she says.

For instance, Fruzsina’s opinion about the influx of migrants differs from Prime Minister Orban’s.

“The government, they made this fake idea like [the migrants] wanted to stay,” she says. “So some believed, ‘Oh, they are coming here to take our jobs and take our country, take our religion.’”

Beginning last June, she and her father, along with other members of their church, began helping refugees at train stations and border-crossings in Hungary and its surrounding countries. Fruzsina says she heard not one express a desire to stay in Hungary. Many of them had no idea which country they were in. Most were headed to the more prosperous Germany, which received nearly 450,000 first-time asylum applicants in 2015, the highest number by far of any European Union member state, according to Eurostat.

Fruzsina and her father take turns reminding each other of favorite memories from the different borders, ranging from simple conversations to close calls. Ivan recalls driving through a field one night near the Serbian border with a car full of Afghan migrants who had become separated from their family members in the dark. After a frantic search and a near-arrest at the crossing, the relatives found each other.

“I was crying,” he says, remembering the moment when the family’s patriarch embraced him in wordless gratitude.

Ivan thinks most Hungarians are afraid of Muslims, and he acknowledges that before last June he lacked any experience with refugees from Muslim countries. But he worries about the Muslim-Christian opposition that appears in the political rhetoric, calling this a “problem.”

“I see persons — men, women, children, families — and it’s very important to love them,” he says. “Doesn’t matter what kind of religion they are in.”

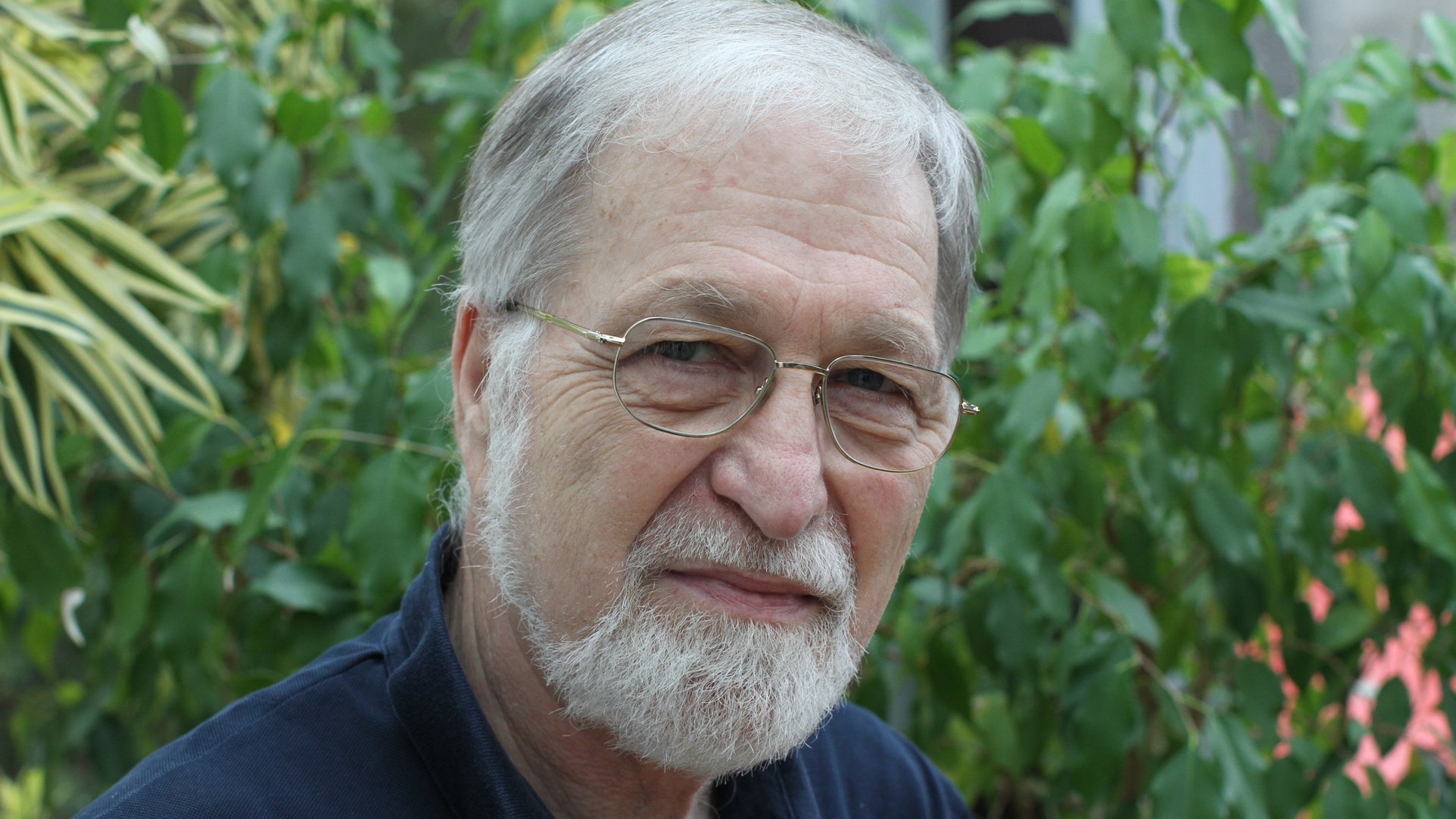

Ferenc Vidor, 92, remembers the day the American Army liberated him from the Mauthausen concentration camp in Austria.

“Eighth of May, 1945,”says the Hungarian Jew, speaking slowly. “I was half-alive at that time, 30 kilograms (under 70 pounds); very, very bad conditions. But my type is a thin type. I survived.”

Before Mauthausen and during the German occupation of Hungary, Vidor and many other Hungarian Jews had been taken to work at labor camps along the Hungarian border with Austria. He was put to work digging ditches in the town of Fertorakos with about 2,000 other young men. But he counts himself lucky.

“The survivors were around 50 percent in Fertorakos,” he says. “In the other villages, a lot of them, survivors were 10 percent, 20 percent, from 1,000 to 2,000 people. The majority died or were killed or (died from) diseases.”

After his liberation, Vidor returned to Budapest to become an architect, urban planner and professor — careers that also took him to Austria, Turkey and Iraq. In addition to Hungarian, he speaks English, German and French. His life experiences lead him to feel sympathy towards the refugees.

“The prime minister of Hungary was terribly against those newcomers,” he says. “In my opinion, those people – they’re living in a civil war in Syria. We have to do our best, helping them as far as possible.”

But Vidor says this idea is unpopular among average Hungarians. In fact, he believes the Hungarian government and media have sought to stir people against the migrants by saying that the foreigners are dangerous.

“The government newspapers say that you should be afraid,” he says.

He brings up the refugee resettlement plan proposed by the European Council, in which every member state was called upon to assist with the resettlement of a total of 160,000 refugees in the European Union.

“Hungary should also accept one of the programs,” he says.

But Hungary and several other countries have opposed any implementation of refugee quotas by the Council.

“That’s a shame,” Vidor says.

Erika Matyas, Vidor’s caretaker, disagrees.

“I think they should not stay here, because, first of all, I don’t think it’s another country that could heal and fix these problems,” says the 64-year-old, speaking through a translator.

Matyas understands that there is an innate response to flee when war strikes one’s home country, but she believes this will only lead to further problems.

“I was just thinking another day: in this way, all the cultures in the world will crumble,” she says. She believes that when individuals leave their native country – the land, their homes, their birthplace, everything they first worked for — more is lost than gained.

Matyas recognizes that Hungary does have many citizens from other cultures – she specifically mentions those of Chinese and Iraqi descent — but she thinks this influx of refugees is different.

“When the Chinese came and they settled here, they brought something with them,” she says. “But these people now, they bring their own problems, and for us it won’t make the country better. They bring their problems and distress with them.”

For this reason, she supports the Hungarian government’s response to the refugee situation.

“There is a line that you have to draw,” she says.

“Hungary drew the line right there, because that’s what the country could take.”

Renata Vitai, a 46-year-old IT manager, brims over with knowledge about Hungary, from historical dates and political trends, to railway routes and popular candy bars. Since she lives and works in Budapest, she also vividly remembers the flood of refugees that came through the city last year.

In the Pope John Paul II Square, she describes how the trees became clotheslines, as migrants camping in the park washed their dirty garments and hung them on the branches to dry. At the Keleti Square railway station, she recalls how refugees filled the underground passageways, sleeping on the ground or in tents.

But now the parks and stations are empty, and as Vitai walks through the city, she shares facts about her native country, interspersed with examples of the stereotypical comments attached to Hungarian culture.

“If there’s a rule, Hungarians try not to keep it,” she laughs. “They try to go ‘round.”

“They’re always complaining,” she adds, walking towards the grand Matthias Church in Buda’s Castle District, west of the Danube River. “That’s why they’re leaving the country. There’s nothing wrong with the country.”

Earlier, while sitting in a café, Vitai explained that her job requires her to attend many meetings. “So,” she says, “if there’s anyone who is not going to say anything in a meeting, it’s a Hungarian.” Vitai says this is an attitude left over from the communist era, when Hungarians were taught not to express their opinions.

Later, as she heads back toward the metro station by the river, Vitai mourns the drab exteriors of the flats lining the quiet cobblestone road.

“In Hungary,” she says, “people don’t put flowers outside their houses, because they would be stolen.”

She wants her two children to study abroad, because she worries that the “Hungarian negativity” is starting to rub off on them. Her concern is not without foundation, since out of all the European Union member states Hungary ranks fourth to last in reported life satisfaction and first in suicide rates, according to data from the European Commission and the World Health Organization.

Vitai knows personally the value of leaving Hungary, since she has had the opportunity to travel to many other countries herself, even working as an au pair for a family in the U.S. during her twenties. After comparing her nation to these places, she now believes Hungary is not as different or special as some Hungarians – such as Prime Minister Orban – may think.

“Orban is very national-minded,” she says, then laughs.

“I think everyone would walk around in traditional clothing if he had his way.”

Istvan Horvath, 54, says there are three minarets in Hungary that are relics of the 150-year-long Ottoman Turk occupation. The distinctive towers, built as part of mosques, have balconies from which Muslims are called to prayer.

Horvath, who holds leadership positions in two international evangelical associations, counts off the three cities where the towers still stand:

Pecs, a southern city with a population of about 160,000, where a mosque built in the late 1600s retains its original minaret.

Eger, a northern city one-third the size of Pecs, where the northernmost Turkish minaret stands alone in the middle of a narrow street.

And Erd, Horvath’s hometown just outside of Budapest, where the third minaret remains, surrounded by power lines.

Each tower, though architecturally beautiful, points to an especially violent period in Hungarian history.

“Like ISIS now, it was Turks here,” Horvath says. He lists rape, sex slavery and the use of child soldiers as a few of the tactics that contributed to Ottoman domination and that are currently employed by the Islamic State group.

When the Ottoman Empire reached the height of its power in the 16th and 17th centuries, its territory extended from southeastern Europe to western Asia, from the Middle East to North Africa. The Turkish armies never pierced the heart of Europe, and Hungarians would say this is because their tiny country bore the brunt of the assaults.

“Hungary said, ‘We are the watchdog of Europe,’” Horvath explains. “We held back the Turks for hundreds of years.”

But the Hungarian army eventually succumbed. Outnumbered and ambushed, their forces fell first at the Battle of Mohacs in 1526. Then in 1541, the Ottomans succeeded in occupying the city of Buda (now the western half of Hungary’s capital city, Budapest). After that infamous siege, Turks ruled in Hungary in some capacity until 1718.

The minarets appeared during this era, visible signs of the widespread shift from Christianity to Islam that took place. But the country is also marked by the memory of what disappeared. Horvath recalls taking a visit to the Hungarian countryside where his host, a Calvinist priest, told him there had been 43 villages in the area before the Ottoman occupation. Afterwards, only four were left standing.

“It was our experience with Muslims,” Horvath says, keen on giving context for the anti-Muslim sentiment expressed by the prime minister and other Hungarians. He has heard the criticisms of non-Hungarians, such as his fellow members of the World Evangelical Alliance. (Horvath serves as secretary general of the Hungarian branch.) Several of them called his countrymen “selfish” and accused them of being cold toward those escaping violence in the Middle East. Horvath sees this as an unfair judgment, and he thinks more Europeans are beginning to understand the Hungarian point of view.

Despite his concern about the growing Muslim population in Europe, Horvath began working with refugees four years ago. He helps at an integration center in Budapest, where they are only allowed to serve refugees seeking asylum, not economic migrants.

When Muslim refugees flooded into the country last year, he took part in the relief efforts. Besides providing the refugees with shelter, water, and halal food sent from an Austrian Muslim organization, Horvath and other Hungarians prepared different greetings for the foreign masses. He roughly translates one of the messages:

“Sorry for your trouble; that you had to leave your home country. We are Christian; we would like to pray for you.”

Laszlo Korossy, 30, remembers growing up in the United States and feeling different. His parents, both immigrants from Hungary, raised him to be “very Hungarian.” He learned Hungarian before learning English, drew in “History of Hungary” coloring books, listened to Hungarian records, and watched Hungarian cartoons. But he also fully experienced American culture, going to school, playing video games and watching “Everybody Loves Raymond.”

When he first visited Hungary as a kid with his parents and three siblings, Korossy said his feeling of other-ness finally made sense.

“To be Hungarian is to be very different,” Korossy says in an interview over Skype, speaking from his home in Maryland. The husband and father of two teaches political science at University of Maryland-Baltimore County and University of Maryland-College Park, and he will soon have a Ph.D. in public policy.

As a teenager, he began to really take interest in his heritage, so he put together a personal website where he could collect information about Hungary. When he wanted to create a section about the Hungarian National Anthem, Korossy could only find rhyming translations available in English. So, he took it upon himself to write a literal translation.

“That’s really all I was intending to do as a snotty little high school kid,” he laughs. “I was trying to sit down and translate this for my website so that there would be something closer to the original meaning. I did not realize that there, up till now, has been no literal translation of the Hungarian anthem.”

That early foray into translation work eventually led to a more recent project, the translation of a Hungarian epic titled “The Siege of Sziget.” In both the anthem and the epic, the subject matter is dark.

Take these few lines from the Hungarian National Anthem, “Himnusz” (Korossy’s translation):

Castle stood, now a heap of stones

Happiness and joy fluttered,

Groans of death, weeping

Now sound in their place.

And Ah! Freedom does not bloom

From the blood of the dead,

Torturous slavery's tears fall

From the burning eyes of the orphans!

“The Siege of Sziget,” which takes place during the Ottoman era, is equally grim.

“(The hero) kills the sultan, they end up routing the Turkish forces, but they’re all gunned down,” Korossy says. “And generally speaking, that’s what passes for a victory in Hungarian history.”

Korossy’s experience living with both Hungarian and American influences sharply highlights the differences between the two cultures.

“There’s a saying in Hungary, ‘Hungarians only laugh while crying.’ It’s heavy stuff,” he says. “And that’s completely at odds with the American mentality of ‘just celebrate’ and ‘be gung-ho’ and if you’re going through something bad, then just buck up and plow through it.”

“It’s a completely different sort of way of looking at the world,” he adds.

These differences carry over into the way the two countries respond to immigrants.

“The same steps that would be taken in America to show assimilation do not necessarily, I think, show assimilation in Hungary,” Korossy says, “because to be Hungarian is a qualitatively different thing than it is to be American.”

America, he says, is unified by a shared idea, which is codified in the Constitution, but Hungarians are unified by shared blood.

“We don’t have this 200-year-old Constitution that we’re all very proud of, that our military swears to uphold, that is greater than any person or any thing,” he says. “What we have is our nation. We don’t have anything else.”

To Korossy, this explains why Prime Minister Orban responds to the refugee crisis by saying that Hungarians need to protect their country and culture.

“Incoming immigrants, migrants, refugees, everyone, I think, have a greater chance to disrupt that than they do in the U.S.,” Korossy says.

For this reason, Korossy sees Hungary’s anti-refugee stance not as a case of racism or even of Islamophobia, but as a matter of politics and national identity. When viewed through that lens, Viktor Orban’s hardline stance on refugees could be seen an attempt to protect the idea of a nation built on a shared ethnicity.

“Maybe that’s a primitive notion, but you can’t discount it,” he says.

“That’s human, and that’s what has kept Hungary together for a thousand years.”

Zoltan Bezeczky recently finished reading the short story “Bernice Bobs Her Hair” by F. Scott Fitzgerald. He did not enjoy it.

“The two girls had conflict,” he says. Bezeczky, who is 20, thinks people should not undermine each other.

He studies Linguistics at Pazmany Peter Catholic University in Budapest. Each school day, he rides the train into the city from his hometown, about 25 miles away. His last name is Polish, but he is native Hungarian.

“Hungary is a monocultural country,” he explains. Quite different from the United States, he adds. Bezeczky is not yet fluent in English, so he takes time before answering questions, carefully searching his mind for words.

“When the refugees came to this country, we couldn’t handle it,” he says. “I think the people started to get a little bit scared.”

Over 1.2 million people applied for asylum in European Union countries in 2015, about 175,000 of them in Hungary, according to Eurostat. That works out to over 17,000 asylum applicants per million Hungarians, which is the highest number relative to population of any EU member state.

“Of course you’re sad about these people,” Bezeczky says, “but I think we should handle this a different way.” He thinks world powers such as the U.S. and Russia could have tried harder to broker peace in Syria. And though he is “not a fan” of Prime Minister Orban’s party, he thinks they may have found the right solution for immigration in Hungary.

“I have no problem with people from different races, but I am sensitive about my culture,” he says. For the immigrants who stay, he thinks it would be important for them to assimilate, but admits it would be difficult.

“Our culture is quite individual,” he explains.

Hungarians frequently are described as pessimists; Bezeczky says this is true.

“Where does it come from?” he wonders.

“Probably our history.”

Ilona Tarr, 59, grew up in Hungary during the communist era, which began after World War II and lasted 45 years. In fact, she was born just six weeks before the country’s 1956 revolution, when Hungarians rose up against the Soviet Union.

Tarr’s father, a small-town priest, was called on to join the protests, but his newborn daughter was sick with an infection, so he stayed behind.

“Because of that, my dad did not end up being in prison,” Tarr says through a translator, referring to the brutal Soviet retaliation that followed the uprising.

Tarr shares stories with vivid details, her memory sharpened from years spent as a museum professional and tour guide. In one such story, she recalls the consequences of her refusal to perform with the school choir at a civil wedding ceremony when she was in grade school. The communist regime took control over churches and frequently clashed with the Catholic church, which resisted control.

“My father said, ‘No, you can’t go to a wedding that takes place without God,’” Tarr remembers. “So I didn’t go. And that was a big problem.” As punishment, she recalls she was made to kneel on the ground and hold both arms above her head for the entire class period.

At university, she earned degrees in Hungarian literature, ethnography and museology, though she says she narrowly escaped being kicked out of the program after she was seen at communion. After graduation, she worked in the Ethnographic Museum at the Hungarian Parliament for six years, in the Department of Textile Collection. The collection featured many beautiful materials, folk costumes and other textile items, mainly from what Tarr and other Hungarians refer to as “greater Hungary.”

“Hungary before the First World War was three times bigger than it is today,” she explains.

This is a sore subject among Hungarians. Talk to any native for very long and there is a good chance they will bring up the Treaty of Trianon, the peace agreement drafted at the end of the World War I. In addition to stipulating various reparations, the treaty drastically re-drew the borders of the kingdom of Hungary and reassigned two-thirds of the land to neighboring nations. Certain populations of native Hungarians suddenly found themselves living in newly enlarged border countries such as Romania, Yugoslavia and Czechoslovakia, many of which have since been further split.

“Those borders after the First World War were drawn in such a way that it went through a village in certain places,” Tarr says. “They took a Hungarian village and actually half of it belonged to Czechoslovakia, another half of it to Soviet Union. And the relatives could not visit each other.”

The official narrative is that Hungary became an ally of Germany in World War II solely to regain possession of those lost territories. Some regions were reclaimed during the war, but nothing could be held permanently.

Tarr says that in communist Hungary, the government suppressed anything that could remind the people of greater Hungary. The goal was for Hungarians to lose the culture that was connected with those territories.

“The best of this nation, throughout its history, was always destroyed,” she says.

As an ethnographer, she saw herself as a protector of whatever best parts of the culture remained. And she thinks Prime Minister Orban does a good job protecting the culture today through his stance on refugees.

“Viktor Orban gave a speech,” she says, referring to the prime minister’s 2016 State of the Union address, “and when he referred to the refugee problem, he said that in the place of our hearts, there is no stone beating, but neither do we have stone in our heads.”

She thinks that for assimilation to occur, immigrants or refugees must fully adopt the culture of Hungary – language, loyalties, religion and all. But she does not see this happening with the refugees in Hungary, specifically those from Muslim countries.

“They want to live according to their own laws and their own culture,” she says.

“If they were few in number,” she adds, “it might be possible (to assimilate.)”

“But coming in masses like this?”

Ivan Lux is 69 years old, but he carries himself like a man 10 years younger. Last year, he retired from a long and successful career as a physicist, working for the most part at the International Atomic Energy Agency in Vienna. He and his wife of 40 years now live in Budapest, where Ivan was born and where they can spend time with their two daughters and five grandchildren.v

Although he spent many enjoyable years living outside of Hungary for his career, Lux says he has never considered settling anywhere else. Even so, he describes Hungary as a difficult nation.

“I would say that this is a very good area for people who want to study soul and peculiar thinking,” he says, “because the Hungarian people are always more pessimistic than the rest of the world.”

“We always think of the shady side of the world, not of the bright future,” he adds.

Though Lux does not consider himself a pessimist, he finds it difficult to say anything positive about the recent state of affairs in Hungary. He is convinced that Viktor Orban’s government exploited the refugee crisis for political purposes.

“The refugees were just tools to frighten the inhabitants in Hungary and convince them that they need the care of the government,” he says.

“From the very beginning,” he continues, “the [state-owned] paper said that the refugees are dangerous, they want to take our jobs, they want to rape our wives, they hide terrorists.”

He admits that to make Hungarians afraid of foreigners is quite an easy task.

“We do not really like foreign people, and we don’t like anything which is different,” he says.

Besides this, he thinks Hungarians naturally gravitate toward leaders with authoritarian personas, like Viktor Orban.

“Hungary never left feudalism, totally,” Lux says. “This is a half-feudalistic country, in the sense that people really expect somebody to lead them, to tell them what is good for you, what is bad for you, where we go together.”

He refers to the nation’s history of being under rule, arguing that the result is a people who are used to being led.

“Therefore, democracy is not a real must for the Hungarian people,” he says.

He accuses the Hungarian government of negatively impacting every sector: education, public health, employment, foreign relations and more. And he worries that if Orban continues to resist the refugee quotas handed down by the European Council, then Hungary will lose the EU funding that has enabled much of the country’s recent development.

Even so, Lux holds on to hope, remembering how encouraging it was to see many Hungarian civil groups volunteering to help the very migrants being demonized in the press.

“The real problem now is there is no leading personality, leading force for these non-complying or oppositional movements,” Lux says. For Hungary to be great again, Lux believes that a new leader must rise to unite the opposition against Orban and his political party.

“This is nowadays the only hope.”

Agnes Toth, 31, works as international coordinator for the Balassi Institute, a government organization headquartered in Budapest that promotes Hungarian culture worldwide. It has cultural centers in 24 countries and Toth oversees the operations of the centers in Istanbul, New York, London, Delhi, and Cairo. The Istanbul location celebrates its 100th anniversary this year.

The name of the institute comes from a medieval-era Hungarian poet, Balint Balassi, whom Toth describes as her country’s version of Johann Wolfgang von Goethe of Germany or Miguel de Cervantes of Spain, their countries’ literary giants.

“His name is well-known abroad – of course, not like Cervantes or Goethe, because Hungary is a little country,” she laughs.

In fact, Hungary occupies a little less space than the state of Indiana. And it is not only the country that is small.

“Hungarian is such a small language,” she says. “It’s just spoken in Hungary, so you cannot use it anywhere else in the world.”

Hungarian is an incredibly challenging language, in terms of both grammar and pronunciation, but Toth shares a theory that this complexity has strengthened Hungarian culture in another way.

"The brain of Hungarian people is working so hard during the whole day to be able to speak Hungarian,” she explains, “that it affects our creativity as well. So we are trying, always trying to find new solutions, new things.”

“And if you look at our history,” she continues, “let it be the number of Nobel Prizes that our scientists won during the last decades, or let it be just the general life for example during the socialist period, we were always trying the find the little holes in the system to stay at least a little bit free.”

Toth sees herself an optimist, so it pains her to talk about the negativity for which Hungarians are known, and she wishes they would relinquish their preoccupation with the past.

“I think if we would look a little bit on the other side of the world, we would see those people – what they live, what they experience, and how they suffer or survive,” she says. “Then maybe we would give a little bit different evaluation of our circumstances.”

“Maybe we would say, ‘OK, maybe we were on the losing side in some parts of the history, but we are still here,’” she continues. “We lost a lot of territory after the Second World War, but we are still here, and we can live in peace.”

When she considers what it would take for the refugees to integrate into Hungarian culture, Toth emphasizes learning the language.

“I think it’s essential,” she says.

She has many foreign friends who have built successful lives in Hungary. They started by learning the language, then formed friendships with native Hungarians, then pursued opportunities in employment or education.

“Nobody cares where they’re from or what religion they belong to or if they pray five times a day or not,” she says, because these people came individually. This is what makes the migrant topic problematic, she says.

“It’s a completely different thing if you have to accept hundreds and thousands of people who are completely different from you.”

Buffett student projects include: Nicaragua: Channeling the Future | Chiapas: State of Revolution | Two Borders | Puerto Rico: Unsettled Territory | Stateless in the Dominican Republic | South Africa: At the Crossroads of Hate and Hope | South Africa Documentary | Borderlands Photo Essays | Divided Families (PDF) | Divided Families Documentary | Children of the Borderlands | South Africa Project

Cronkite News is the news division of Arizona PBS. The daily news products are produced by the Walter Cronkite School of Journalism and Mass Communication at Arizona State University.