Visual Story

Visual Story

A Community’s Response:

Reflections from the White Mountain Apache Tribe a year into the COVID-19 pandemic

The coronavirus pandemic hit Native Americans especially hard.

But as the spotlight turned to larger communities like the Navajo Nation,

the much smaller White Mountain Apache Tribe, in eastern Arizona,

quietly battled to save its people.

Photos and text by Alberto Mariani/Cronkite News | May 4, 2021

WHITERIVER – Last year, the community of 15,000 in eastern Arizona was considered a hotspot. By Sept. 1, five months after its first recorded COVID case, the tribe had 2,400 cases and had lost 39 people. Over the next six months, there were 1,500 new cases and just 10 additional deaths.

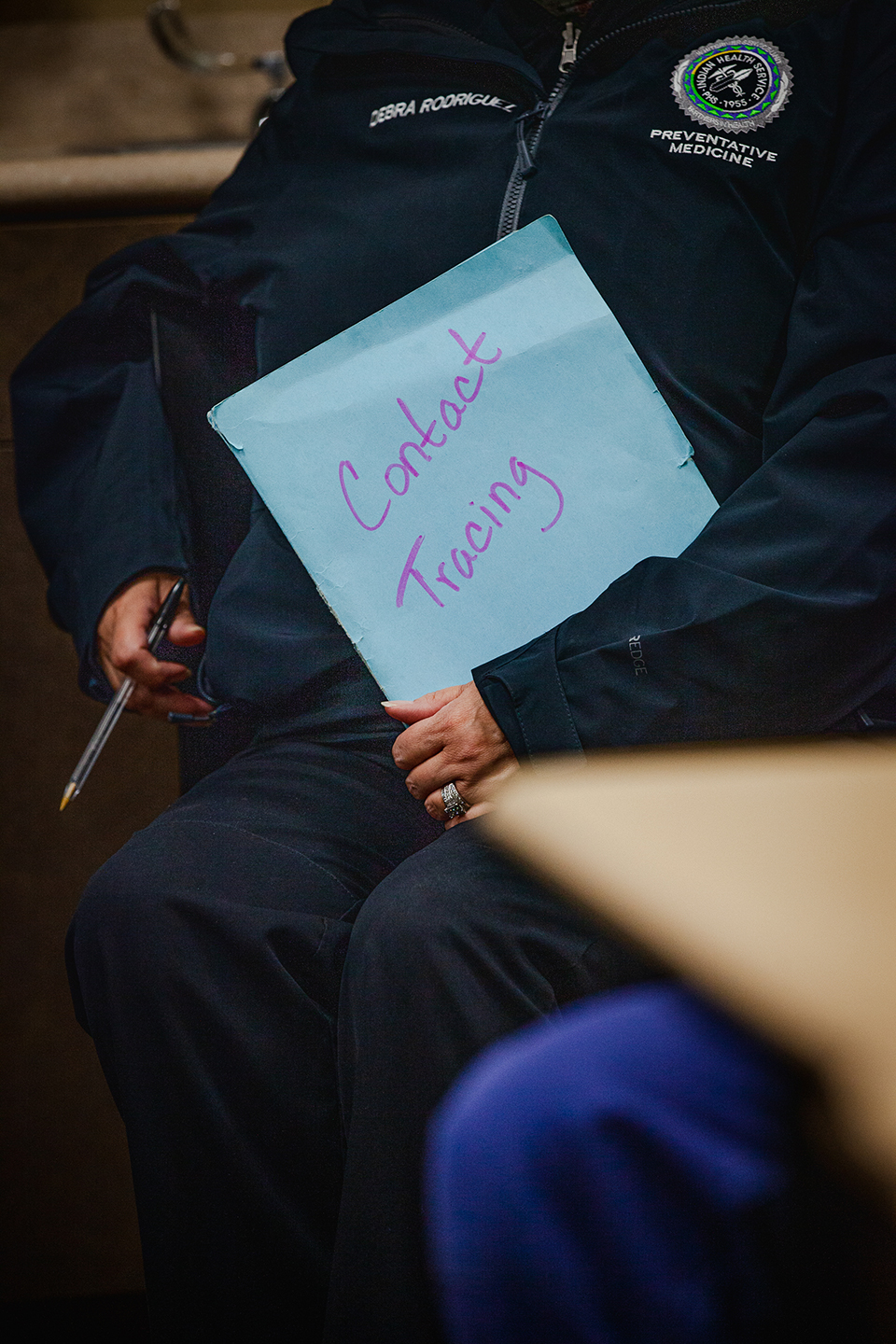

The tribe slowed the spread of the disease and helped curb death rates through a combination of intense contact tracing, surveillance of high-risk individuals, and vaccinations.

Systemic social and health inequities, along with multiple generations all living under one roof, put rural communities like this one at greater risk from the virus.

Even as new cases have eased up, the routine that made the decline possible remains.

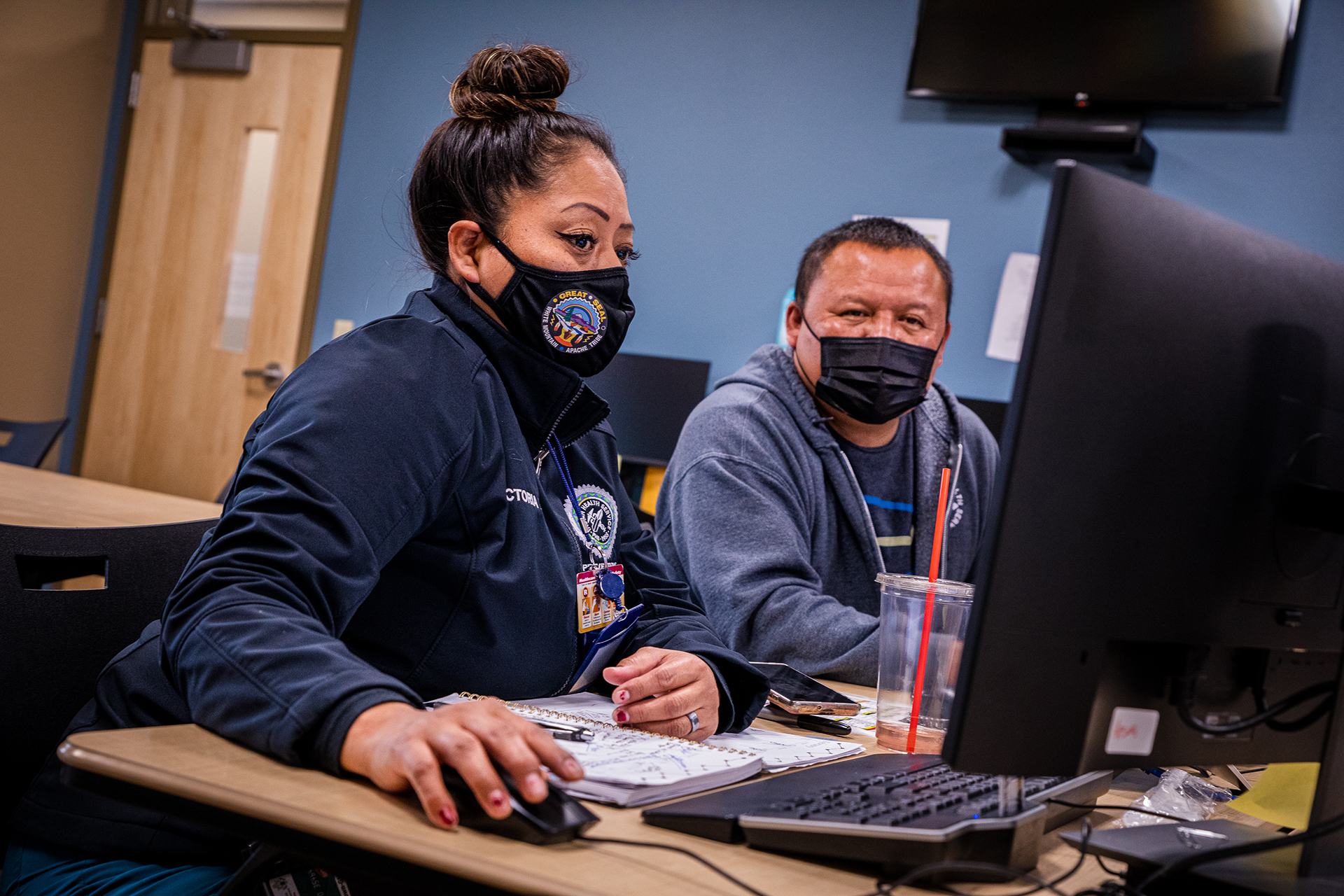

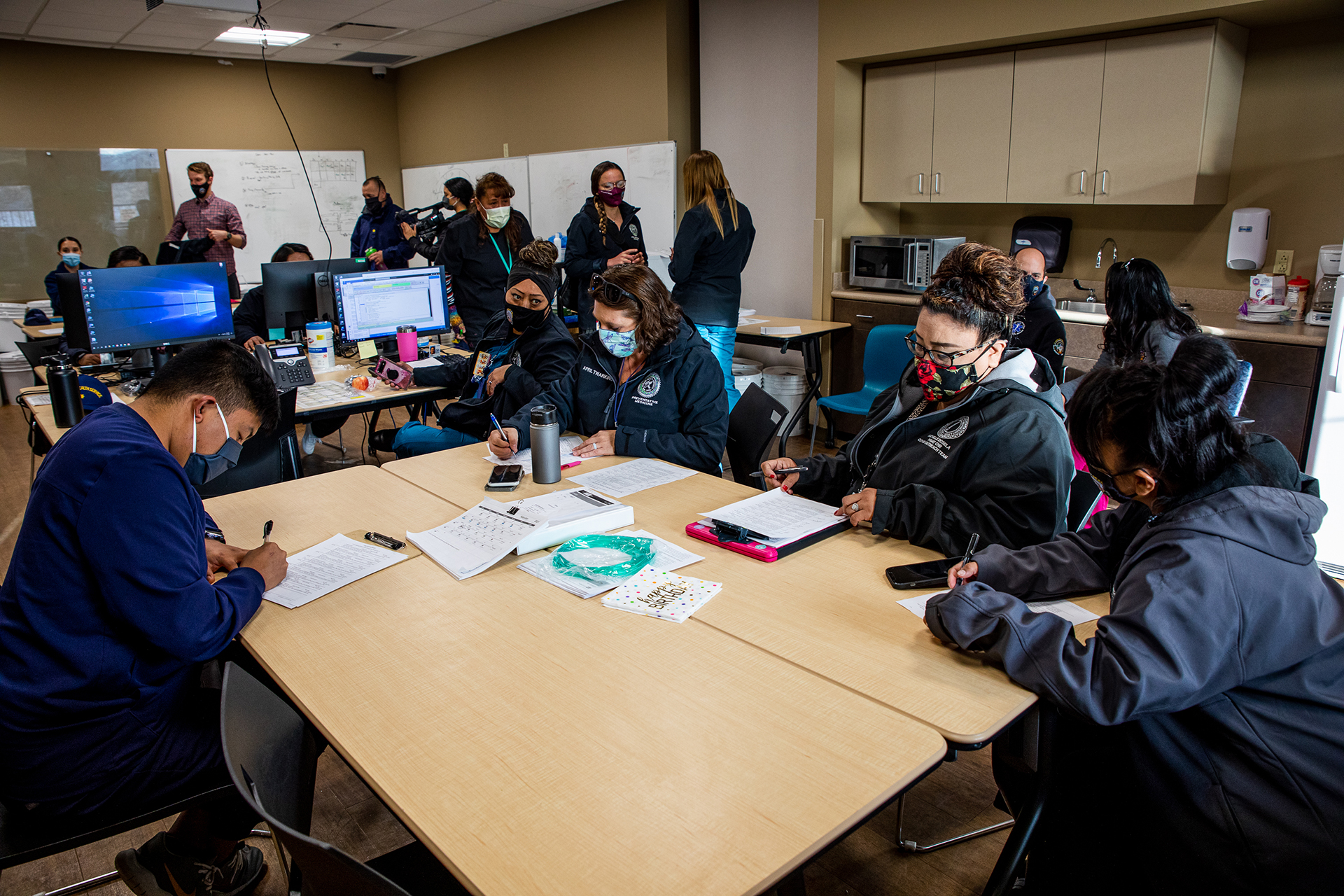

Each day at 9 a.m., a team of medical professionals and tribal members gathers at the Whiteriver Indian Hospital to evaluate the spread of the virus. The morning session lasts about half an hour, then staff are assigned cases to follow up on.

They separate into smaller teams and head out across the reservation, going door to door to check on those who are positive with COVID-19, to monitor vital signs of those at-risk, and to vaccinate those who agree.

Early on, the medical team started using pulse oximeters to assess patients’ vitals more accurately and spot positive cases before more pronounced symptoms developed.

This unique outreach effort helped the team form a stronger bond with tribal members, something medical workers say allowed them to get better information about who might have been exposed to the virus and respond quickly to any deteriorating cases. Cronkite News asked some of these health care workers to jot down reflections of lessons learned throughout the pandemic and then share those in personal audio recordings. Listen on next slide.

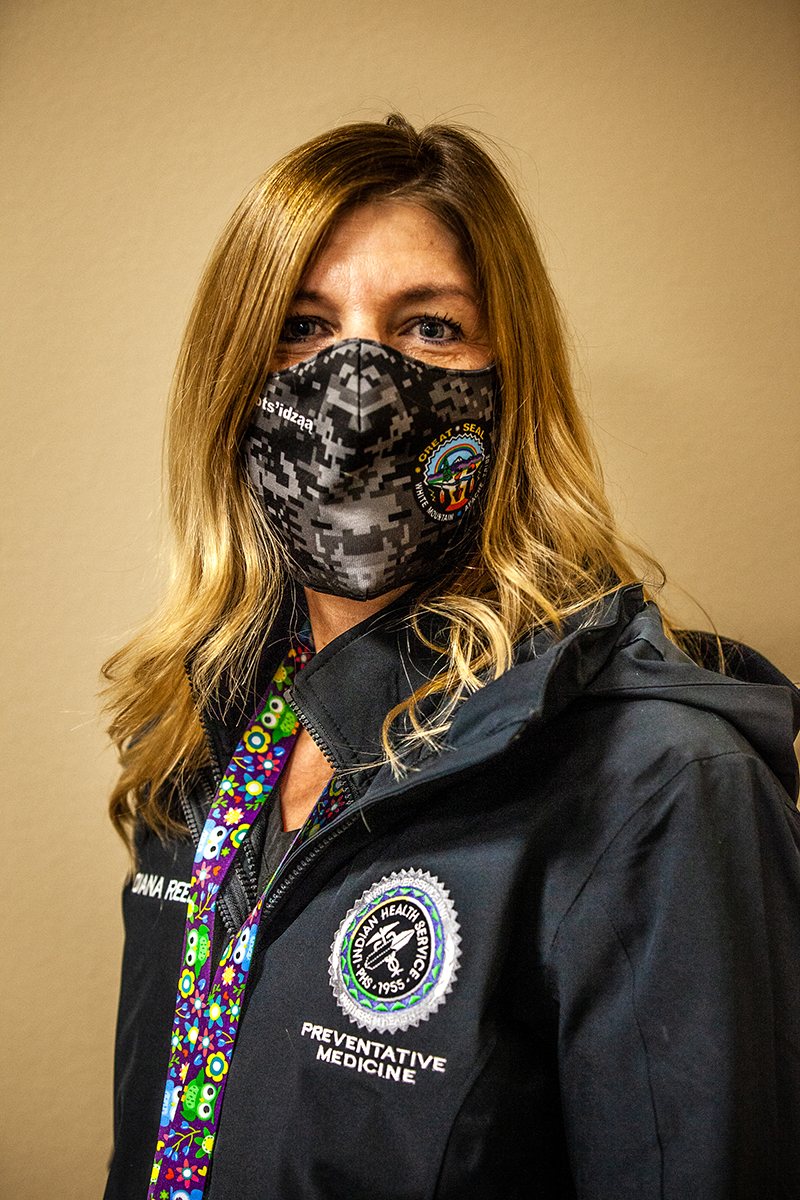

“As nurses we are taught to develop trust with our patients, and that has never been more needed than now.”

– Diana Reed, public health nurse, Indian Health Service

“I realize how many lives have been saved due to seeing them before the symptoms are too bad.”

– April Twarkins, registered nurse, Indian Health Service

“I think the community was happy to see that a tribal member was there to help, and that, too, made them more comfortable.”

– Victoria Moses, contact tracer, Indian Health Service

“We wouldn't have been able to … test, trace and chase the virus … if we didn't have buy-in from both the community and the community leadership.”

– Dr. Ryan Close, director of preventative medicine, Indian Health Service

Now that vaccinations are underway, that bond has been a valuable tool to deter skepticism about whether COVID vaccines are safe. Kristen Parker, an outreach director for the U.S. Public Health Service, says that everyone in the community has been touched by tragedy during the pandemic. But now that she is able to deliver vaccines, she says, “It feels amazing to be part of the solution.”

Once vaccines became available, health care workers started offering shots by going straight to residents’ houses. Often more than one person is vaccinated during a single visit, because not everyone can easily get to community vaccination events.

On this day, Bonnie Lewis got her second shot – completing her vaccinations series – and she encouraged her neighbors to do the same. “Go ahead and get it, because a lot of my family members have got COVID-19 and a lot of us have ended up in the hospital. That’s what happens if you don't,” she said.

Bernard Henry, a father of nine, was scheduled to get his first shot when this photo was taken. While he remains wary of potential side effects, he feels relieved about getting vaccinated. He got COVID but experienced only mild symptoms. His wife, however, was hospitalized last year.

Even though some skepticism about the vaccine persists in the community, medical officers say they are confident they will be able to vaccinate most people.

By the end of April, more than 7,000 tribal members were fully vaccinated and no new COVID deaths had been reported in months. The medical staff and tribal leaders take pride in how they combated the disease, but will never forget those who perished.

Dr. Ryan Close, director of preventative medicine for the Indian Health Service in Whiteriver, said the pandemic exposed everyday health disparities between urban and rural communities, as well as rich and poor. He hopes that health care professionals apply some of the lessons learned from the pandemic to ensure better health outcomes for all in the future.

“The spread of COVID-19 throughout the world was exacerbated by the gaps between public health and health care,” he said, “previously invisible and now glaringly obvious.”