Monica Simpson, executive director of the reproductive justice organization SisterSong, speaks to the crowd at a Juneteenth celebration in her hometown of Wingate, N.C. (Photo by Shelby Rae Wills/News21)

Activists unite to fight maternal mortality post-Roe

Black women are far more likely to die of pregnancy-related causes than white women across the U.S. In the South, activists and providers are working to overcome these disparities, which they worry will worsen amid abortion bans.

Our content is free to use with appropriate credit. See the terms.

WINGATE, N.C. – We’re experiencing a “major crisis in this country,” says Monica Simpson, the executive director of SisterSong, an Atlanta-based reproductive justice organization advocating for better maternal health care for people of color in the South.

“Maternal health in this country is something that I’m glad that we’re now finally talking about, and SisterSong has been one of those organizations for many years now really sounding the alarm,” Simpson said in an interview with News21.

The U.S. maternal mortality rate is the worst among wealthy nations across the globe, research shows. It’s a problem many fear will worsen as states ban abortion in the wake of the reversal of Roe v. Wade.

In 2021, the latest year for which data is available, the maternal mortality rate was 32.9 deaths per 100,000 live births, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. That’s compared with 23.8 in 2020 and 20.1 in 2019.

The rate for Black women was far higher: 69.9 deaths per 100,000 live births.

And yet the CDC reports that over 80% of pregnancy-related deaths are preventable.

For years, North Carolina’s maternal mortality rate exceeded the national average.

But Dr. Elizabeth Cuervo Tilson, state health director and the chief medical officer at North Carolina’s Department of Health and Human Services, notes that’s shifted.

“We have been doing a lot of work over the past 10 years, and so our disparity ratios are greatly decreasing,” Tilson said. “We still have much, much more work to do, but we are better than the overall nation.”

Black women in the state die almost twice as much as white women, Tilson noted. But that, too, has improved.

“If you go back to our data from 2001 to 2004 … Black women were dying at six times the rate than our white women, and now we’re down to 1.8,” she said.

These are some of the people behind the change:

Tina Braimah and Amber Rodriguez run Sankofa Birth and Women’s Care center in Durham. Both are midwives and mothers who offer midwifery and health services from a cozy residential office.

“A lot of people don’t realize that midwives do more than just birth, that we can do contraception and we can do STD testing and we can do gender-affirming care,” Braimah said. “There’s so many other things that are within the scope of our practice that we may not necessarily get to do in a traditional setting.”

Amber Rodriguez, left, and Tina Braimah pose on the porch of Sankofa Birth and Women’s Center, which is located within a neighborhood to ensure it is accessible to the community. (Photo by Shelby Rae Wills/News21)

Braimah said midwives can provide most of the services that doctors do. “Everything that you would have done with your physician – as long as you have a low-risk pregnancy – I as a midwife can provide that for you.”

She said from her perspective, “everyone should have a doula and a midwife” for their birthing experience.

Iesha Lynch is a birth, death and postpartum doula in Roanoke Rapids. She was motivated to become a doula after suffering complications during and after the birth of her son, Carmine.

Advocating for birthing people is a large part of her work.

“I just want all birthing people to know that you are in your right to fight for your right, to speak up for yourself, to stand up for yourself, to advocate for yourself – for you and your family members – and that you are not in the wrong,” Lynch said.

“If you don’t have anyone that’s listening to you, go find someone who will. They don’t, then find another one. They don’t, then find another one, because eventually you will find someone who will.”

Lynch’s own pregnancy went smoothly – until her water broke. Her birthing plan had to be dismissed after her son passed a stool while still in the womb, putting him at risk of fetal distress and requiring her to undergo a cesarean section.

Soon after giving birth, Lynch’s incision popped open. Doctors discovered placenta had been left in her body during delivery. She also developed a complication called postpartum preeclampsia.

Lynch said she had a difficult time convincing doctors that something was wrong until she was in dire circumstances. Her experience is too common among Black women.

“My birth story is an example (of) how this society and our medical system does not listen to Black women and … Black birthing people and what they are saying is happening to their bodies,” she said.

Iesha Lynch is a birth, death and postpartum doula in Roanoke Rapids. She was motivated to become a doula after suffering complications during and after the birth of her son, Carmine.

Advocating for birthing people is a large part of her work.

“I just want all birthing people to know that you are in your right to fight for your right, to speak up for yourself, to stand up for yourself, to advocate for yourself – for you and your family members – and that you are not in the wrong,” Lynch said.

“If you don’t have anyone that’s listening to you, go find someone who will. They don’t, then find another one. They don’t, then find another one, because eventually you will find someone who will.”

Lynch’s own pregnancy went smoothly – until her water broke. Her birthing plan had to be dismissed after her son passed a stool while still in the womb, putting him at risk of fetal distress and requiring her to undergo a cesarean section.

Soon after giving birth, Lynch’s incision popped open. Doctors discovered placenta had been left in her body during delivery. She also developed a complication called postpartum preeclampsia.

Lynch said she had a difficult time convincing doctors that something was wrong until she was in dire circumstances. Her experience is too common among Black women.

“My birth story is an example (of) how this society and our medical system does not listen to Black women and … Black birthing people and what they are saying is happening to their bodies,” she said.

Part of Iesha Lynch’s practice includes creating art for her birthing patients, such as this watercolor painting of a patient’s placenta. (Photo by Shelby Rae Wills/News21)

‘An issue that everyone should care about’

This legislative session, North Carolina passed Senate Bill 20, which has two main components: an abortion ban after 12 weeks and measures meant to reduce maternal mortality rates.

The bill was vetoed by Gov. Roy Cooper, a Democrat, but that was overridden by the Republican-controlled Legislature.

Rep. Julie von Haefen, a Democrat, opposed the bill because of the abortion restrictions. The measure also increases funding for prenatal providers and care, and makes it easier for midwives to practice by removing a requirement that they be supervised by a physician.

North Carolina Rep. Julie von Haefen, a Democrat, fought against the state’s new abortion ban. (Photo by Shelby Rae Wills/News21)

“It’s unfortunate that they put these maternal health aspects into Senate Bill 20, because if they really wanted to help moms and babies, there are so many other ways that they could have done that,” she said.

“They were just giving us crumbs to kind of compensate for a really terrible piece of legislation that’s really going to harm people.”

Von Haefen said the issue of maternal health “shouldn’t fall on the shoulders of just Black women.”

“This issue shouldn’t be partisan, and it shouldn’t be based on race. It shouldn’t be based on your sex. It’s just an issue that everyone should care about.”

Creating ‘good support systems’

“Every election cycle, there’s promises of what people are going to do and not do, and Black people are still at the bottom of those promises,” said Maya Jackson, founder and executive director of Mobilizing African American Mothers through Empowerment – or MAAME.

Maya Jackson, founder and executive director of MAAME Inc., walks through a Durham neighborhood with her daughter, Aminah. (Photo by Shelby Rae Wills/News21)

Jackson founded the Durham-based organization – which provides pregnancy counseling and support, mental health services, and supplies such as diapers, wipes and formula – after her own terrible birthing experience.

“While I was in the hospital, the nurse forgot to massage my uterus, so I had been hemorrhaging for a while,” she recalled. “Thankfully, it wasn’t so severe that I had to get a blood transfusion, but it was still just an awful experience.

“And I started to learn that this was a shared experience for Black women in this country.”

According to North Carolina’s latest Maternal Mortality Review Report, hemorrhaging is the leading cause of pregnancy-related deaths in the state.

As Jackson spoke to more parents and community organizers, she saw the need for a resource center to improve maternal experiences and foster community.

Maya Jackson cradles her 8-month-old, Zarah, while she talks about her work at MAAME. (Photo by Shelby Rae Wills/News21)

“The biggest thing that I want for … Black women to really pay attention to is: taking care of themselves, resting, not being fearful of what’s to come, but just being proactive and making sure that they are mentally and emotionally supported,” she said.

“I want them to feel empowered. I want them to feel seen. I want them to be loved up on and to be nurtured.”

Prioritizing joy in reproductive justice

Simran Jain and Maya Hart are co-workers at SisterSong and helped out with the group’s Reproductive Justice Bus Tour, which stopped in Wingate, N.C., on June 17, 2023. (Photo by Shelby Rae Wills/News21)

Maya Hart, left, and Simran Jain goof around as they clean up after the Sistersong Reproductive Justice Bus Tour launch. (Photo by Shelby Rae Wills/News21)

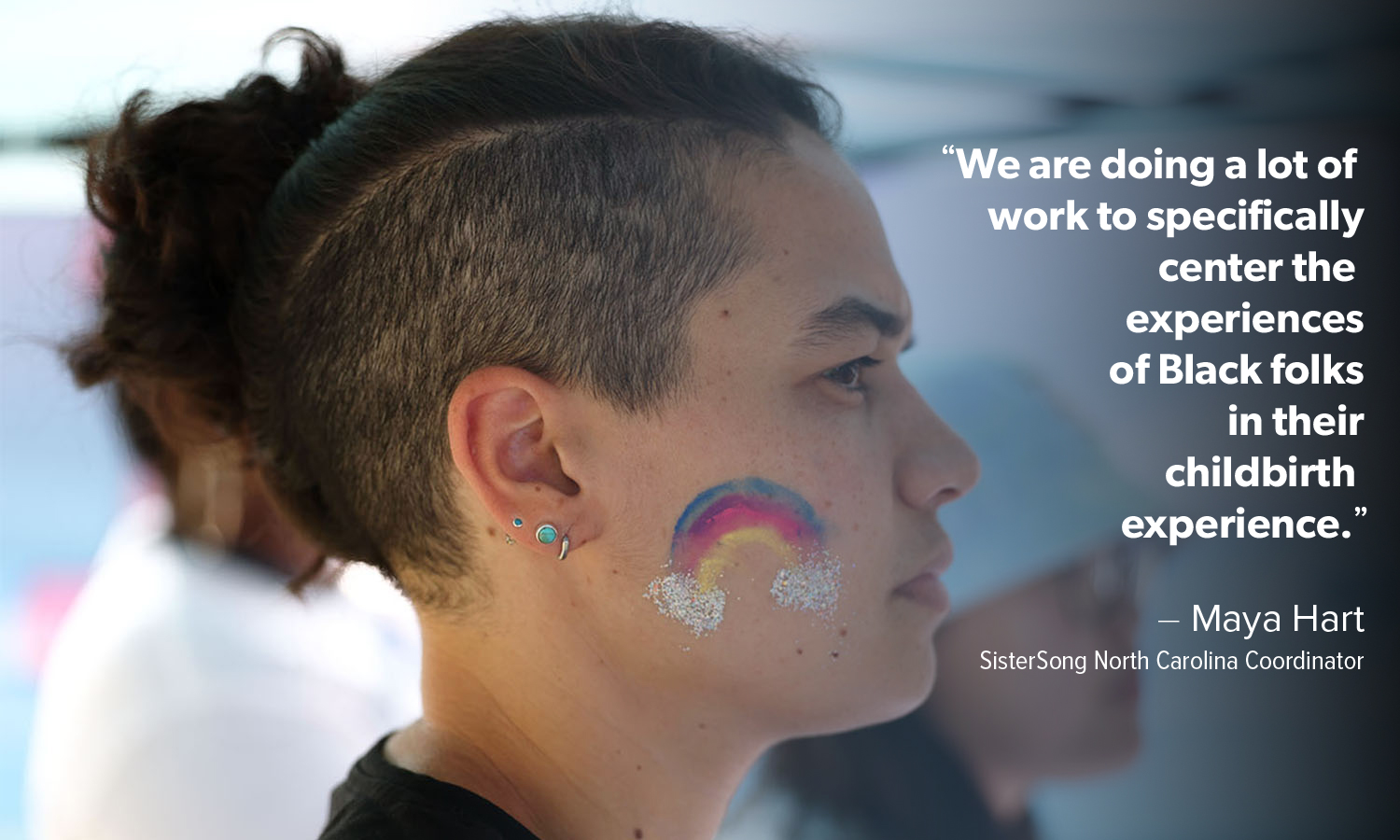

Maya Hart, SisterSong coordinator for North Carolina, said it’s important to include maternal mortality as part of the reproductive justice conversation.

“We are doing a lot of work to specifically center the experiences of Black folks in their childbirth experience, because we know the racial disparities in health outcomes – not just for mothers but for babies, as well.”

Hart describes themself as a multiracial, Black, queer mama, birth worker and reproductive justice organizer. Since becoming a parent, they shifted their birth work to focus on postpartum support, lactation education and mutual aid.

In 2021, Hart started Diapers for Black Durham, a local fund providing free diapers, wipes and lactation support for Black families across Durham County.

Tilson, the state health director, said North Carolina has started repairing the maternal mortality disparity through partnering with local health departments, increasing access to medical care, providing training and support for providers, prioritizing women, and collecting, publishing and assessing data to foster improvement.

“The Southeast overall has had a long legacy of health disparities,” she said. “And so to address those health disparities that have multiple, multiple drivers we really need to address it in a multifaceted way.

“If North Carolina can do better than the country and have a lower disparity than the country, if we can do that with all the complicated issues that run into it, then any state can do that.”

Maya Hart, SisterSong coordinator for North Carolina, said it’s important to include maternal mortality as part of the reproductive justice conversation.

“We are doing a lot of work to specifically center the experiences of Black folks in their childbirth experience, because we know the racial disparities in health outcomes – not just for mothers but for babies, as well.”

Hart describes themself as a multiracial, Black, queer mama, birth worker and reproductive justice organizer. Since becoming a parent, they shifted their birth work to focus on postpartum support, lactation education and mutual aid.

In 2021, Hart started Diapers for Black Durham, a local fund providing free diapers, wipes and lactation support for Black families across Durham County.

Tilson, the state health director, said North Carolina has started repairing the maternal mortality disparity through partnering with local health departments, increasing access to medical care, providing training and support for providers, prioritizing women, and collecting, publishing and assessing data to foster improvement.

“The Southeast overall has had a long legacy of health disparities,” she said. “And so to address those health disparities that have multiple, multiple drivers we really need to address it in a multifaceted way.

“If North Carolina can do better than the country and have a lower disparity than the country, if we can do that with all the complicated issues that run into it, then any state can do that.”

This summer, SisterSong held a reproductive justice bus tour with stops in cities across the South – from Durham to New Orleans. Each event focused on sharing information, creating a sense of community and offering free resources and food.

The event was a way to “bring our people together,” said Simpson, the executive director, “to let people experience joy … just to really understand what is happening in our communities every single day.”

News21 reporters Jada Respress and Peyton Brooks contributed to this report.

(Video by Jada Respress and Peyton Brooks/News21)

Our content is free to use with appropriate credit. See the terms.