(Video by April Pierdant and Kevin Palomino/News21)

Mexican abortion-pill networks reach across U.S. border to help immigrants without access

Mexico decriminalized abortion just before the United States went the opposite way and ended federal abortion rights. Now activists are helping people in the U.S. get abortion pills to those in need via cross-border underground networks.

Our content is free to use with appropriate credit. See the terms.

MONTERREY, Mexico – Verónica Cruz Sánchez watched something remarkable happen from the office of her women’s rights organization in Guanajuato, the capital city of one of this country’s most conservative Catholic states.

Founder of Las Libres – “the free” in English – she had built an underground abortion-pill network in a country where having the procedure could have meant going to jail.

But in September 2021, from the central Mexican mining-turned-tourist town, where colorful houses paint the hillside in reds, oranges and blues, Cruz Sánchez saw everything change.

The Mexican Supreme Court issued a surprise ruling that abortion was no longer a crime – not even in places like Guanajuato, where it continues to be outlawed by the state.

That same month across the border in the U.S., Texas instituted a so-called “fetal heartbeat bill” that effectively outlawed abortion.

And the Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health Organization case was before the U.S. Supreme Court, with the potential to reverse Roe v. Wade and end almost 50 years of abortion rights in America.

“It was crazy,” Cruz Sánchez said. “For those of us working in abortion, the example to follow was the United States. All the countries in Latin America wanted a Roe … we wanted to have the constitutional right.”

But suddenly it was Mexico at the vanguard of abortion access.

Cruz Sánchez reached out to other groups that distributed abortion medication in Mexico, as well as abortion rights organizations she knew in the United States, and started to build the “red transfronteriza” – the cross-border network.

“We could give them all the support and training,” she said. “How do you find the medication? … How do you do the logistics so the pills get into the hands that need them? How do you guarantee security for everyone?”

And she had a specific U.S. population in mind.

“We knew there was a large proportion of undocumented Hispanic immigrant women from Central America who cross through Mexico all the time,” Cruz Sánchez said. “And that was one of our motivations for why we wanted to support Texas – not only for all women but especially for undocumented immigrant women.”

“In terms of abortion, Texas has a lot of complexities. The people there are paralyzed right now by the legal situation.”

— Verónica Cruz Sánchez

Founder of Las Libres

Groups from the U.S. and Mexico decided to meet in Mexico in January 2022, but a snowstorm moved their encounter to Zoom, where the U.S. women signed in with their cameras turned off. No names were displayed. Nothing was recorded.

The Texas law, Senate Bill 8, included civil penalties for helping people obtain an abortion. The irony wasn’t lost on the Mexican participants. The United States, known to them and the entire world as the land of the free, had driven its citizens into hiding over abortion rights.

“They had so much fear,” said Vanessa Jiménez of the abortion pill network Necesito Abortar, based in Monterrey. “That, for me, was the biggest impact – to understand a little bit what fear they had for the authorities in the United States.”

Just months after that first meeting, Roe v. Wade was reversed, the fear worsened, and the work of the cross-border network began in earnest.

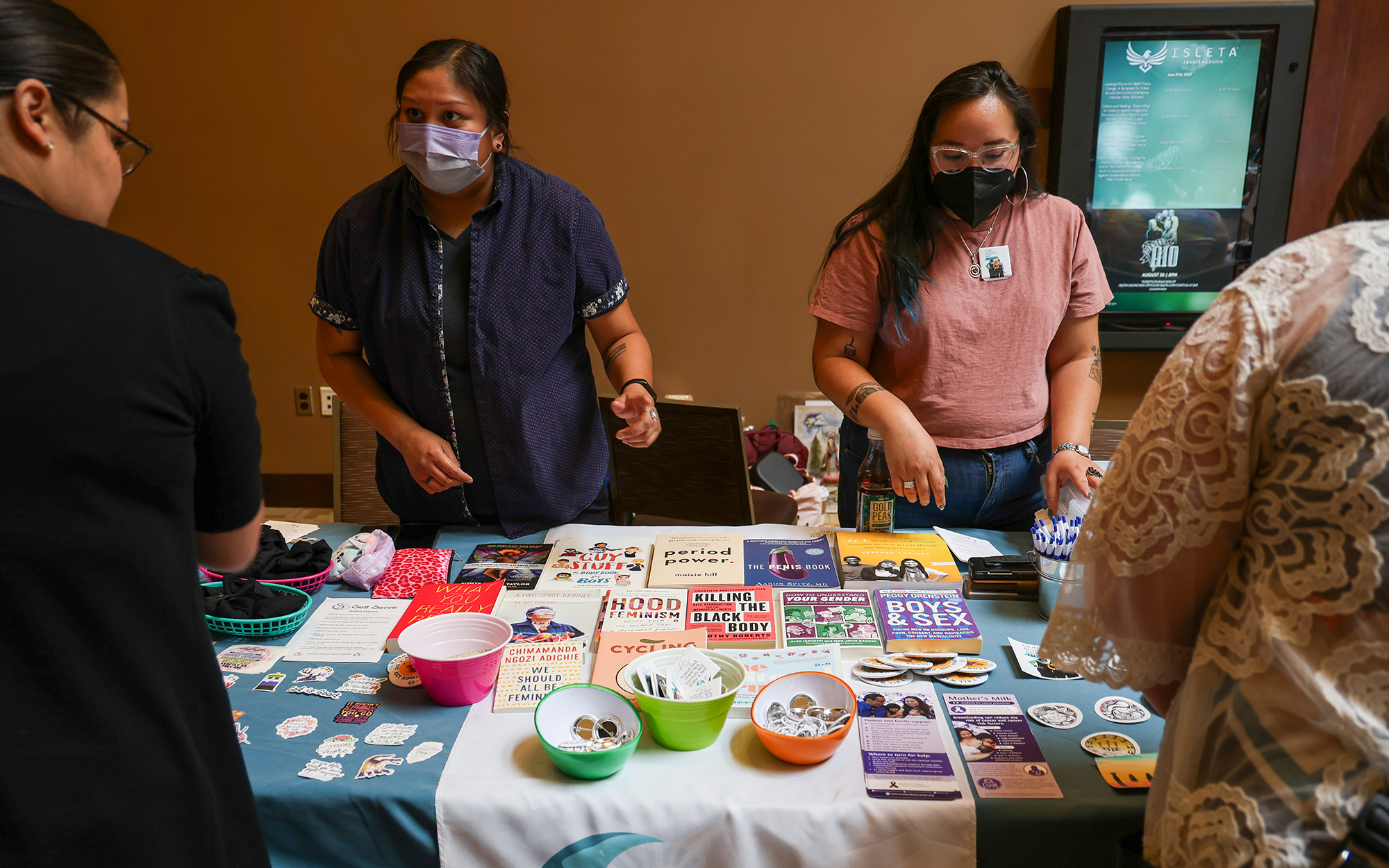

Vanessa Jiménez runs an abortion pill network called Necesito Abortar from her home in Monterrey, Mexico. Jiménez has an informal network of family and friends who take pills into the United States during visits over the border. (Photo by April Pierdant/News21)

‘I can take pills’

In a residential neighborhood with a full view of the Cerro de la Silla, Monterrey’s iconic mountain peak, Jiménez runs Necesito Abortar out of her spouse’s family home. The living room, with its colorized photograph of her in-laws’ wedding and the family portrait of sisters in matching red dresses, has been converted into her office.

There, she stuffs manila envelopes to create at-home abortion kits for delivery. Each includes small bags containing a single, round-shaped mifepristone; four tiny misoprostol pills; two oval-shaped ibuprofens; and four sanitary napkins.

In the U.S., the Food and Drug Administration has approved a regimen of mifepristone and misoprostol to terminate pregnancies up to 10 weeks and says it is both safe and effective.

Jiménez has an informal network of family and friends who take these kits and vials of pills into the United States during visits over the border.

“Recently I was talking to a girl who told me, ‘I bring things from the United States and sell them. … If you want, I can take pills,’” she said. “This is how we have made these alliances.”

A picture reads “Abortion: Free and Dignified” at Necesito Abortar in Monterrey, Mexico. (Photo by April Pierdant/News21)

Once the pills arrive, Jiménez accompanies patients through the abortion process by phone.

There’s nothing illegal about carrying medication over the border; Americans cross into Mexican border towns all the time to buy drugs that would otherwise require a prescription in the U.S.

But giving pills to someone in Texas to end a pregnancy could land you in jail.

“Someone could be charged with a crime in Texas for providing those abortion pills to someone else in Texas to self-manage their abortion,” said Blake Rocap, legislative counsel for Avow, an abortion advocacy group based in Austin, Texas.

Individuals could also face civil penalties under Texas’ SB 8. In one ongoing case, a Texas man sued his wife’s friends for wrongful death after they helped her obtain abortion pills.

Despite this, volunteers have stepped up to work with the cross-border network as “acompañantes,” people who not only provide abortion medication but stay through the process by telephone, using guidelines from the World Health Organization.

“We had to explain things. … What is misoprostol? What does it do? Can you detect it in the body? How does it function?” Jiménez said. “In the end, I believe, the purpose was not to solve the problem in the United States but rather to share the experience that we have so that there, in their own context, they can form the networks that exist here.’’

News21 tracked down and interviewed a Mexican woman who volunteers as an “acompañante,” carrying pills into the U.S. She gets her supply from Las Libres, and pregnant people in the U.S. reach her via social media to request the medication.

The acompañante said she started her fight for reproductive rights after her own pregnancy at age 23, which she carried to term because of the stigma surrounding abortion. She said she has no fear of crossing the border with pills.

“I do it out of passion,” she said, “with the conviction that I’m not doing anything wrong. The laws are what need to change.”

One recent weekend, she made the five-hour drive to El Paso, Texas, and dropped medication with her U.S. distributor.

“I do it out of passion, with the conviction that I’m not doing anything wrong. The laws are what need to change.”

— A volunteer acompañante

The distributor gets two to three requests a month for pills in states like Texas, Kansas and Arizona. If there’s a request in New Mexico, just across the stateline from El Paso, she goes in person. Otherwise she mails the pills using the U.S. Postal Service, because private carriers require personal information.

“I am not the only one,” the distributor said, adding that volunteers tend to be professional women in positions of power who can take on the risk. “There are other people who receive a lot of requests, and they try to spread them around so that the weight doesn’t fall on one person.”

Both the acompañante and the distributor requested anonymity out of fear of legal repercussions in Texas.

“As mothers, aunts, friends – in our reproductive life we had access to abortion, with access to reproductive health measures that many women now do not have,” the distributor said. “So, I think we feel a bit indebted for having been able to take advantage of the law in those years.”

Since its birth last year, the cross-border network has earned significant news coverage in U.S. media outlets, and with it, more clients. People find the network through Reddit, Instagram, and Facebook, and order pills via encrypted messaging apps like Signal and WhatsApp.

Post-Roe, Las Libres has seen requests for abortion pills from the U.S. explode – from 10 a day to 300 in some instances, putting stress on the organization’s supply, Cruz Sánchez said. The group now uses cash donations to buy pills, in addition to help from international nonprofits.

But the network has fallen short in one area.

“Everyone thought that since we were a Spanish-speaking organization in Mexico, most of the people in the United States who were going to look for us would be Spanish-speaking, undocumented immigrants,” Cruz Sánchez said, adding: “The majority only speak English.”

Cut off from care

Cathy Torres runs an abortion fund in South Texas’ Rio Grande Valley, the delta of the river that divides the U.S. and Mexico. Of 1.4 million people living in the land dotted with palm trees and citrus orchards, at least 10 percent are in the country illegally.

Torres, organizing manager of Frontera Fund, said the demand for travel abortions in the region went from eight a year before the Texas ban shut the only abortion clinic in the Valley to 15 a month. The closest access state, New Mexico, is a 12-hour drive, and she was flying people as far as Las Vegas and Virginia.

“All the way leading up to the night before June 24th, 2022 … I funded my last abortion and flight at like 2 in the morning,” Torres said.

She wanted to work as long as she could in anticipation of what came later that day: the Dobbs ruling eliminating the constitutional right to abortion.

“And sure enough, I think it was 9 or 10 in the morning, we just had to stop,” she said.

Cathy Torres, based in Texas’ Rio Grande Valley, is the organizing manager for Frontera Fund, which pays abortion costs for Texas residents. (Photo by Kevin Palomino/News21)

Torres says the demand for travel abortions in the Rio Grande Valley went from eight a year to 15 a month after the state’s six-week abortion ban took effect. The closest access state, New Mexico, is a 12-hour drive, and she was flying people as far as Las Vegas and Virginia. (Photo by Kevin Palomino/News21)

People living in the country illegally have always been cut off from health care services because of poverty, language barriers and fear. They are ineligible for federal health care programs and are often hesitant to sign up for state benefits or even seek care at hospitals because of concerns over deportation.

Health care advocates have had to be creative to reach these communities. When the National Latina Institute for Reproductive Justice started working in the Rio Grande Valley over 15 years ago, its members canvassed neighborhoods in an ice cream truck, announcing meetings in homes or community centers to talk about reproductive health care.

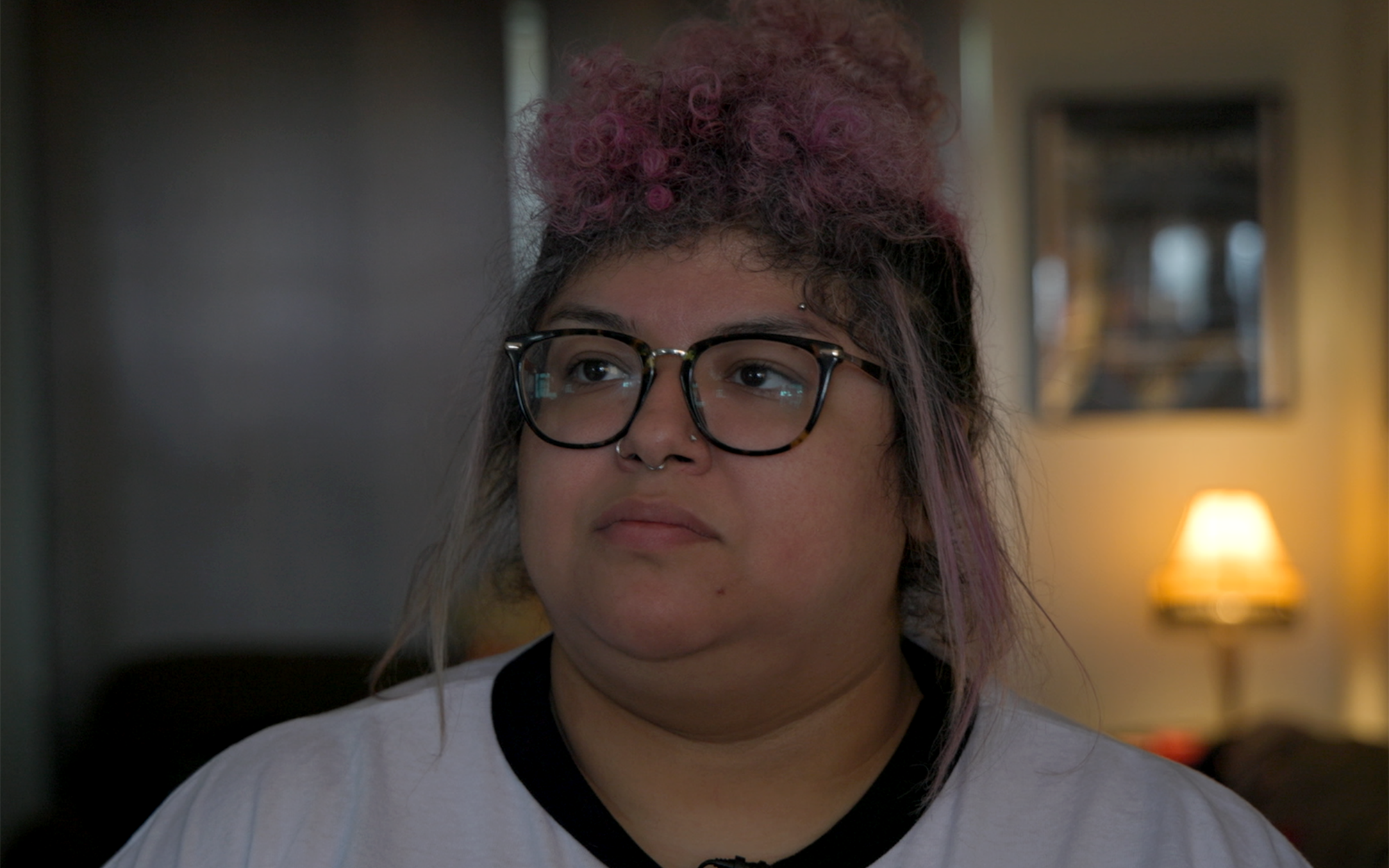

“You get snacks and play games like Lotería or whatever. And that’s kind of how these conversations started,” said Nancy Cárdenas Peña, campaign director for Abortion on Our Own Terms, which advocates for self-managed abortion through medication.

Nancy Cárdenas Peña is an advocate for reproductive justice and self-managed abortion in Texas’ Rio Grande Valley. (Photo by Kevin Palomino/News21)

Post-Roe, the barriers for these communities have only become greater.

When Frontera Fund started operating again after Dobbs, it could no longer pay for people to go out of state.

“We legally cannot fund travel or housing or any other practical support just because of how muddy these laws are,” Torres said. “There are aiding and abetting policies in place.”

She said immigrants living in the Valley illegally are “landlocked.” Even if they decide to travel for services, they must pass through Customs and Border Protection checkpoints. And the chances of getting discovered have worsened since 2017, when the Texas Legislature passed SB 4, giving state and local police the authority to stop people and ask for documentation.

“So they’re having to grapple with, ‘God, I either really, really risk it’ or ‘I just stay pregnant,’” Torres said.

And everyone is fearful of the new laws, including doctors providing prenatal care.

“We had a whole handout about what to do about miscarriage or if you find out you’re pregnant, what your pregnancy options were like,” said Dr. Denise De Los Santos, an OB-GYN and faculty member at the University of Texas Rio Grande Valley medical school. “We really wanted to foster that kind of open communication with our patients. And now it’s not like that at all. We have to just be very careful about what you say.”

The obvious option for people who can’t travel is self-managed abortion at home.

As of 2020, medication was used in more than half of abortions in the U.S., according to the Guttmacher Institute, an abortion-rights organization. But with restrictive abortion laws, 14 states now outlaw taking medication to end a pregnancy, according to KFF, an independent health policy group.

“People are taking their health into their own hands,” said Texas Civil Rights Project President Rochelle Garza. “Self-managed abortion is something that is rising as a response to the lack of health care.”

Rochelle Garza is an attorney in Brownsville, Texas, fighting for immigrant civil rights, including access to abortion services. (Photo by Kevin Palomino/News21)

The cross-border network works in the Rio Grande Valley. Couriers from Jiménez’s Necesito Abortar in Monterrey cross into McAllen, one of the main cities.

But ask anyone on the U.S. side about the network, and they go silent.

“It’s this confusion of what is legal – because they’ll say that you cannot get sued for having an abortion, like, you yourself. But we’ve had situations where people have gone to jail for them,” Cárdenas Peña said, referring to the case of one Rio Grande Valley woman who was arrested for murder over an alleged self-induced abortion.

After protests by activists, the charges were dropped.

New efforts

Cruz Sánchez is thinking of new ways to reach people who might need the services of Las Libres or the cross-border network, like asking Texas-based volunteers to place stickers with Las Libres’ social media accounts in bathrooms, bars, restaurants, parks and other public spaces.

She’s also working to reach migrants as they cross through Mexico, in hope they’ll spread word of the pill networks once they arrive in the U.S.

“In terms of abortion, Texas has a lot of complexities. The people there are paralyzed right now by the legal situation,” Cruz Sánchez said.

In the end, it requires going door to door, person to person, like the organization did in Mexico, and getting people in the U.S. to organize and form their own networks.

“We’ll continue to give all the input necessary,” she said. “If Mexico could organize without a single peso, just by organizing the people, obviously the U.S., with more money, can do it. But the big question is: Who’s going to do the groundwork?”

Our content is free to use with appropriate credit. See the terms.