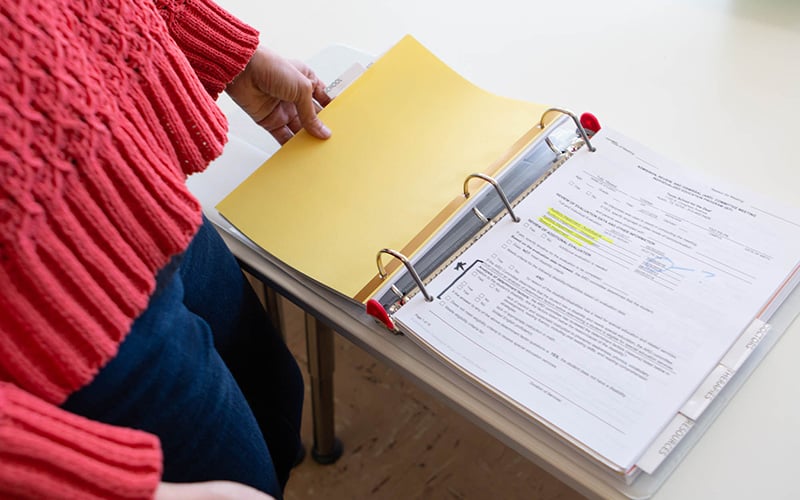

Mothers of children with disabilities meet at VELA in Austin, Texas, to learn how to advocate for their kids. Founded in 2010, VELA serves about 1,500 families a year. “For us from the very beginning, it’s been about giving parents that space where they can really let down their guard and be around others that look and talk like them, so they can speak honestly and feel welcome to share their experiences,” founder and Executive Director Maria Hernandez says. (Photo by Delia Johnson/Cronkite News)

Texas group empowers Latino parents to advocate for children with disabilities

By Miranda Cyr/Cronkite News |

Editor’s note: The mothers in this story agreed to speak only on condition that their last names not be used, due to the immigration status of some families served by VELA.

AUSTIN, Texas – Five years ago, when her son was 4, Fabiola traveled to the United States from central Mexico to seek care for his disabilities: an enlarged spleen, hearing loss, ADHD and developmental delays.

In her home city of Aguascalientes, care was too expensive and difficult to find. Now living in Texas, Fabiola still faces challenges navigating a complicated health system for children with disabilities.

Then Fabiola found VELA, and finally she feels as if she isn’t alone.

“It’s my support group, it’s my strength to continue on, and it’s where they teach me that my child has resources,” she said in Spanish. “VELA teaches us to always be strong for our children.”

Fabiola left central Mexico to find better care for her adolescent son, who has multiple disabilities. VELA provides a support system for Fabiola and many other families who need help in navigating their children's care. The mothers in this story agreed to speak only on condition that their last names not be used, due to the immigration status of some families served by VELA. (Photo by Delia Johnson/Cronkite News)

VELA, which means “candle” in Spanish and doubles as an acronym for Vibrant, Empowered, Limitless, Able, is a nonprofit organization that provides support and resources to mostly Hispanic and immigrant families whose children have disabilities.

The group offers bilingual classes, workshops and community events to educate and empower parents and normalize the issues their children face, said Maria Hernandez, VELA’s founder and executive director.

“The experience of disability is very isolating,” she said. “You also need to learn how to take care of yourself while you’re going through this experience. A big part of doing that is meeting other people that you can sit with, that can look you in the eye and say, ‘Me, too.'”

Founded in 2010, VELA serves about 1,500 families annually – helping to close a significant gap in health care for Latinos and immigrants.

Barriers to timely diagnoses and care for Hispanics with developmental disabilities have been well-documented. Studies show, for example, that Latino children are diagnosed with autism on average two and a half years later than white non-Latino children.

In states with large Hispanic populations like Texas and Arizona, those disparities can be more profound.

“All families with disabilities face obstacles when accessing health care, transportation, interpretation services and social support networks,” states an October 2017 study Arizona State University conducted on behalf of the Arizona Developmental Disabilities Planning Council. “However, discrimination, disenfranchisement, poor self-esteem, lack of community resources, and limited knowledge of existing resources can cause further feelings of isolation in Latino families.”

That’s where VELA and similar organizations come in.

While her 2-year-old son plays, Diana talks with Catalina at VELA in Austin, Texas. The mothers open up to each other about their difficulties incorporating their kids with disabilities into society. VELA tries to give parents not only resources but knowledge about caring for themselves by connecting with others who are going through the same thing. (Photo by Delia Johnson/Cronkite News)

Hernandez said VELA gives parents the power they need to stand up for their rights and their child’s rights. It offers courses on how to read and comprehend school and medical documents, how to find resources that can offer support, and how to take care of their own health while caring for their children.

The first thing new parents receive upon finding VELA is a parent toolkit – an informational binder offered in English and Spanish with resources and statistics meant to educate them before meeting with medical or school officials.

That binder, Hernandez said, “becomes a physical representation that they are the holders of the information. They’re the No. 1 experts on their child.”

When parents have a learning space to interact with people who look and speak like them, she said, they’re able to gain vital support through a community they can relate to.

“Whenever we tell families how many thousands of families are like them, they’re surprised,” Hernandez said, “because they feel like they are the only ones.”

Perla, another mother involved in the organization, said she felt relief when she discovered she wasn’t alone.

Her 13-year-old son has been diagnosed with cerebral palsy, autism and Dandy-Walker syndrome – a congenital brain malformation – and other medical problems. For two years, miscommunication with a doctor in the U.S. led to her son being in and out of the hospital with pneumonia every couple of weeks.

“It’s so difficult when the doctor tells you that your child doesn’t have anything … but you’re seeing the symptoms,” she said. “You know your child, and you know that your child is not all right, that your child is not eating because their throat hurts, that your child doesn’t react the same because of a headache, that your child can’t sleep well.”

Her son is now doing better after switching to a new doctor, but Perla said the experience was “something that no parent wants.”

Mayra, who joined VELA six years ago, said she and her twin daughters have experienced similar problems and discrimination. Her daughters were born in the U.S. after Mayra came from Mexico due to complications with her pregnancy. Her 8-year-old daughters have been diagnosed with autism, but they have received insufficient care, she said.

She recalled pediatricians at times demanding that she and her family speak to them in English.

“When a specialist referred us here to VELA, we discovered that we have rights to be treated like any other person,” Mayra said.

She and Perla faced similar problems in the school system, including officials not being understanding of their children’s conditions and difficulty with communication.

In Texas, nearly 500,000 students were enrolled in special education services for the 2017-2018 school year. According to a study by Education Week, the rate of students enrolled in such programs in Texas is the lowest in the country – 9.2% compared with a national average of 13.7%. In contrast, New Mexico, Arizona and California have rates of 15.8%, 12.5% and 12.2%, respectively.

The Texas Education Agency’s policies came under scrutiny after an investigation by the U.S. Department of Education found that in 2004, the agency urged school districts to limit their rate of special education enrollment to 8.5%. From 2004 to 2016, the percentage of students in these programs dropped from 11.6% to 8.6%, and violated the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act, according to the investigation.

In 2019, VELA’s leaders began visiting schools to raise awareness of the resources they provide. Hernandez said they were able to help an additional 358 families through that outreach.

Thanks to the coronavirus pandemic, that in-person outreach is on hold for now. Texas schools are closed until May 4 due to COVID-19.

Because VELA operates on a six-week cycle, the last group of 100 families “graduated” from the program on March 12, before social distancing advisories were in full effect. Leaders have sent out needs assessments to members to learn more about how they can help while many families are sheltering in place. The organization has suspended in-person meetings until May 4 to coincide with state policy.

“The way that we’ve designed our programming has been through asking the community, so we would do the same in this situation to make sure that we’re designing based on what people need versus what we assume that they need,” Hernandez said.

“The thing that motivates me is to watch them physically, emotionally, mentally transform into feeling powerful. As soon as the family feels like they have what they need, their immediate next question is, `How do I do this for someone else?'”

Connect with us on Facebook.

Leave a Comment

[fbcomments]