The rocket carrying the Phoenix CubeSat, designed and built by Arizona State University students, lifts off from the NASA Wallops Flight Facility on Virginia’s Atlantic coast Saturday on its way to the International Space Station. (Photo by Harrison Mantas/Cronkite News)

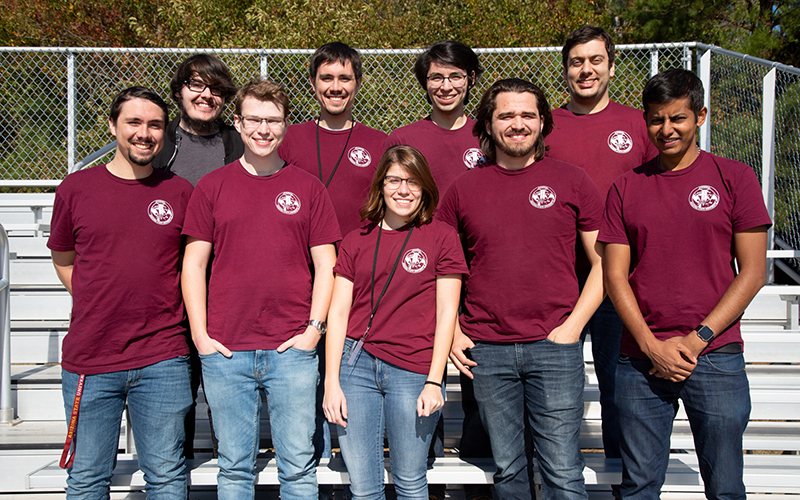

The ASU student team behind the satellits, back row from left, Nicholas Altman, Devon Bautista, Jaime Sanchez de la Vega and Raymond Barakat. Front row, Trevor Bautista, Craig Knoblauch, project manager Sarah Rogers, Ryan Fagan and Vivek Chacko (Photo by Harrison Mantas/Cronkite News)

An unshielded Cygnus space craft being worked on in the hangar at NASA Wallops Flight Facility in Virginia. The nanosatellite built by Arizona State University students, along with six others, was launched Saturday on a similar Cygnus rocket. (Photo by Harrison Mantas/Cronkite News)

WALLOPS ISLAND, Va. – A concussive boom radiated out from the launch pad at the NASA Wallops Flight Facility as nine Arizona State University students watched four years of their work ascend into space Saturday.

“I kind of thought my head would be like a jumble of internal screaming,” said Sarah Rogers, the project manager for the ASU student team. But when the launch came, she said, “My mind was very clear, because you’re just there in the moment sharing it with everybody.”

The students’ project was one of seven so-called CubeSats that were packed into the Cygnus spacecraft as part of a resupply mission to the International Space Station. All seven of the microsatellites launched Saturday were produced by student teams at schools across the U.S.

Those projects – along with supplies, equipment and other experiments on the resupply mission that included live mice and a space oven – docked with the space station Monday.

The bread-loaf-sized ASU satellite, dubbed Phoenix, will live on the ISS until around January when it will be launched into orbit to begin collecting data on urban heat islands: The phenomenon where daytime heat is held by urban roads and buildings, keeping them from cooling off at night.

Rogers is now a graduate student studying aerospace engineering, but started the project as a freshman in 2015. She said the students who have rotated through the project over the years, more than 100 in all, have gained myriad opportunities academically, but stressed what they learned about themselves was equally important.

Phoenix, the “nanosatellite” designed by a team of Arizona State University students to study urban heat islands. (Courtesy ASU Phoenix CubeSat team)

“How you think, how you talk to people, how you analyze what’s in front of you,” were some of the ways Rogers said the project pushed the team members. “I’ve seen so many people grow, and that’s been an incredible experience in itself.”

Ryan Fagan, a team leader and radiometry specialist, said he was surprised how quickly he got to jump into this project when he was a freshman at ASU four years ago.

“They (NASA) gave us $200,000 to build the spacecraft, which is crazy starting out in freshman year,” Fagan said. “We had no idea what we were doing, and it was just so run-and-gun, pick up what you can.”

Students from five different schools at ASU were involved with the project. Engineers partnered with computer scientists, and urban planning students on the nanosatellite that will orbit the earth and use a thermal camera to study urban heat islands in seven U.S. cities.

Beyond its science mission, Rogers says her team is working on an academic paper about the project to help facilitate future ASU CubeSat projects that want to take advantage of NASA’s CubeSat Launch Initiative.

“Everything we’ve learned from Phoenix will make a really significant impact at ASU and hopefully for other universities moving forward,” Rogers said. “The fact that we’ve been able to contribute in that sense feels really incredible.”

The data will last long, but the nanosatellite will not. The rocket was out of sight within minutes after liftoff Saturday, and Phoenix itself is only designed to collect and transmit data for six to eight months before slowly falling out of orbit within two years.

Fagan said his hands-on experience at ASU was different from other projects in that it allowed the students to go beyond just the design phase of the project. On Saturday he got to enjoy the fruits of his labor.

“It didn’t hit me until a few minutes after it disappeared and we were sitting, that it’s done, it’s up there … and I think that’s where I was like, ‘Wow,'” Fagan said.

-Cronkite News video by Bryan Pietsch