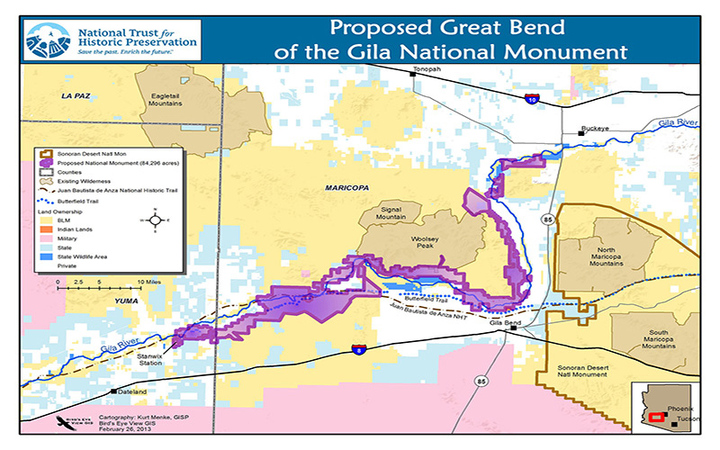

PHOENIX – Native American tribal leaders, archaeologists and Congressman Raúl Grijalva are seeking to designate more than 84,000 acres curving along the Gila River as a national monument.

Grijalva introduced federal legislation to create the monument in southwest Arizona, starting west of Buckeye and extending 80 miles along some of the most arid areas of the state to protect sites considered sacred to 13 tribes.

“Our way of life has taught us to respect the ancient remains of our ancestors that are in these areas,” said Lt. Gov. Monica Antone of the Gila River Indian Community.

Eight of the 13 tribes affected by the proposal have endorsed the creation of the monument. But it isn’t clear whether there is enough support in Congress. Grijalva, an Arizona Democrat, introduced a bill in June to renew the call for the monument. The bill is not scheduled for a Congressional committee hearing in September. A similar bill introduced by Grijalva in 2013 did not make it through Congress.

See related story:

Gallego, Reid call for more protections for federal lands, not less

National monument designations are controversial in the Southwest, including a proposal to add more land surrounding the Grand Canyon. Supporters say they protect valuable natural resources while opponents say they are unnecessary federal land grabs.

Tom Jenney said the Arizona chapter of Americans for Prosperity opposes the creation of the Gila monument.

“The federal government does not need any more of Arizona’s land,” Jenney, who heads the Arizona chapter, said in an email.

The organization prefers that land be privately owned and, if it must be managed by the federal government, that less-restrictive designations including monuments be avoided.

How the monument could change land use

The Great Bend of the Gila National Monument would follow the curves of the Gila River for 80 miles, starting west of Buckeye and going through some of the least-populated areas along the river, said William Doelle, president and chief executive of Archaeology Southwest, which supports the designation and issued a report outlining tribes’ connection to the land.

William Doelle is the president and CEO of Archaeology Southwest, which released a report detailing 13 tribes’ connections to the land in the proposed Great Bend of the Gila National Monument. (Photo by Courtney Columbus/Cronkite News)

The Bureau of Land Management oversees the land that could become a national monument. The federal agency currently manages 12.2 million acres of Arizona land, according to its website.

Dolores Garcia, a spokesperson for BLM, said the agency has no stance on whether a law proposing the national monument should be enacted.

If enacted, the law would prevent any new mining claims from being filed on the affected land. An official with the Arizona Mining Association said its members have no plans to file claims in the area.

Making the land a national monument may not change how the public can use it, Garcia said.

“Oftentimes, public use stays the same,” Garcia said. “Where cultural sites are designated may determine where activities can and cannot take place.”

Tucson-based archaeologist Aaron Wright spent a year working on the archaeology report released in August. Although he said he hasn’t heard any outright opposition to the bill, he said some people are concerned that they will have less access to the area if it becomes a national monument.

When the government gets involved, they tend to shut down use by off-road vehicles, said Jamie Nelson, who owns AZ ATV Rental in Goodyear.

The Arizona branch of the organization Americans for Prosperity prefers that land be privately owned and, if it must be managed by the federal government, that less-restrictive designations including monuments be avoided.

Why tribes support the monument

Archaeology Southwest’s report arose from a year of collaborating with 11 of the tribes connected to the proposed monument, including the Gila River Indian Community, Salt River Pima-Maricopa Indian Community and Hopi Tribe.

The report details the land linked to each tribe to the land and assesses each tribe’s support of the monument. The authors found that each participating tribe supports ramping up the BLM’s cultural preservation efforts.

Doelle said the land within the proposed monument also contains ‘world-class rock art.’

Grijalva said at a news conference that failing to create the monument would leave sacred sites open to abuse, including vandalism and theft.

Sites that are sacred to the Fort Yuma Quechan Tribe would be included in the proposed monument.

Manfred Scott, who chairs the Fort Yuma Quechan Tribe’s cultural committee, supports the creation of the proposed national monument. His wife, Ernestina Noriega Scott, is a member of the Pascua Yaqui tribe. (Photo by Courtney Columbus/Cronkite News)

Manfred Scott, who chairs the tribe’s cultural committee, supports creating a national monument. Scott said people need to understand how much these sacred sites mean to Native Americans. He said off-road riders can damage ancient petroglyphs on the volcanic rocks near the Gila River.