Dirt roads similar to this one in Hidden Valley wind up and down different parts of the neighborhoods. (Photo by Kelsey DeGideo/Cronkite News)

MARICOPA — When Trisha Johnson spotted a Mitsubishi lurching along the dusty road in front of her house, her fingers flew over the keyboard of her smartphone. Within seconds, she posted an alert on Facebook to neighbors in her rural community.

The post was the latest by a private Facebook group that serves as a Frankenstein of resources for this rural community: a news service, community builder and a beacon for help, all rolled onto one page.

What used to be shared across a backyard fence is transformed for the digital age, where neighbors are separated by stretches of land but connected by common needs. The Hidden Valley/Thunderbird Farms neighborhoods, nestled next to the city of Maricopa in the far southeast Valley, are like other small, local communities across the country that are building their own communication system.

“When you belong to this, it’s kind of like an internet neighborhood watch,” Johnson said. “It takes literally seconds for people to see your post in the group, it goes viral.”

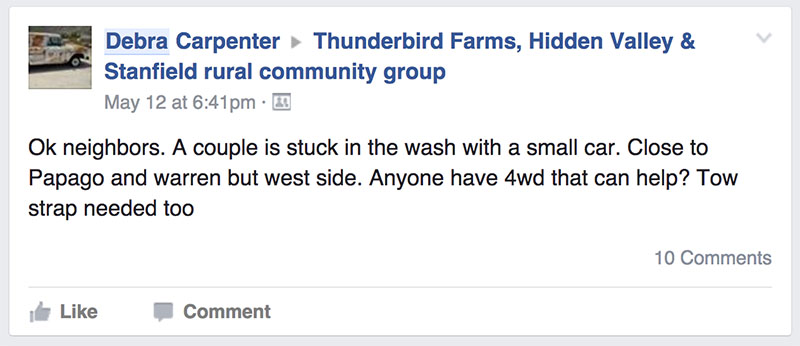

Debra Carpenter, a Facebook group member, alerts the community about a couple whose car is stuck. Residents were to quick to jump on the opportunity to help.

Neighborhood Newscast

More than 500 members of the Facebook group are armed and ready with their mobile phones or internet connection. They live in a rural area of cattle, corn and dust where dirt roads are behind every home, people ride horses and put up signs offering pigs for sale. It’s a region butting up against a growing urban presence of businesses and new homes. It’s the kind of place, familiar in Arizona and elsewhere, where the population of 47,000 doesn’t tell the story of all the spaces in between the people living there.

Hidden Valley and Thunderbird Farms, in the 25-mile radius west of Maricopa and the Ak-Chin Indian Community, aren’t on a map. They don’t often draw the attention of the news media or law enforcement. But to the people who live here, there’s a lot happening.

(Map by Elizabeth S. Hansen/Cronkite News)

Take the night of May 12.

News of a possible crime in Thunderbird Farms was pushed out to the group.

Ideas were thrown out online: “I heard there was a murder,” one user wrote. Another wrote, “I heard someone mention a stabbing out here this morning.”

A flurry of posts described law-enforcement cars blocking a road. Others just wanted an update.

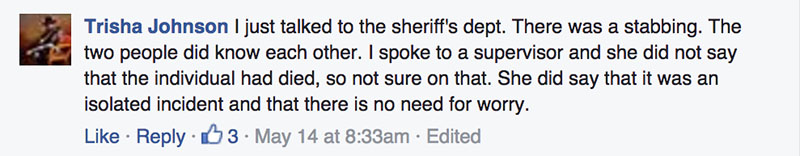

Trisha Johnson, who posts frequently, called the Pinal County Sheriff’s Office. She got back to the group with an initial report.

While the neighbors who read the Facebook post knew everything was under control, others remained in the dark. No press release. Not a single news van. No reporters. But residents learned they were safe.

Four days later, the rest of the world caught up to Thunderbird Farms. Around noon on May 16, PCSO posted a news release on its Facebook page. Azcentral picked up the story later in the afternoon. By then, neighbors had moved on to the next conversation.

“It’s like the community telephone, we all pick it up and listen in,” said Belinda Clifford, an administrator for the Facebook group.

Community members aren’t the only ones listening in.

The Maricopa Monitor, a website and weekly newspaper, has used the group as a reporting tip line.

“It’s where the conversation happens,” said editor Adam Gaub. The Monitor has acted on tips and investigated concerns posted on the page. Gaub believes listening to people on social media is a newer, better way for journalists to highlight community concerns and decide what stories to pursue.

“A journalist is somebody who goes out and spends the time to look into the truth of something and tells it to other people,” said Gaub, who has been covering the region for six years. “This isn’t a full-time job, but they can still do a valuable service for their community.”

This brand of citizen-journalism, Gaub said, also has downsides like spreading gossip, wrong information and inciting arguments.

One member posted accusations of a couple’s affair. Some members chimed in before the post was quickly deleted. In posters’ zeal to watch out for illegal activities, sometimes they label strangers who are just passing through as suspicious.

Exclusive, members-only community

The Facebook group, in a move to keep to its mission, won’t allow just anyone in. Membership is a privilege that is strictly policed by administrators. Requirements include:

- Members must know at least one person who has already been accepted in the group.

- Members must name the cross streets where they live.

- Members cannot be public officials, business owners or any other person who may post biases.

- If a member is caught lying about his or her residence the membership will be immediately revoked.

The requirements were meant to keep members safe but have unintentionally and successfully built a sense of community.

“If we let other people from other areas in then we’re not that community anymore,” said Johnson. “What goes on in town and what goes on out here are two completely different things.”

The connection goes beyond online. Tanya Graeb, a Facebook group member who is a real-estate agent, owns a tack shop that serves as an unofficial information hub. She tells customers who don’t have internet access what’s going on. People often come in to get the latest from the Facebook group.

“I’ve met a ton of people through the community page and now they’re good friends,” Graeb said.