Patty Talahongva, the granddaughter of Rosalie Lalo: “Look at the legacy of the boarding schools. Separation of child from family and community. How would your family survive that? How do generations of that recover?” (Photo by Clarissa Cooper/Cronkite News)

Rosalie Lalo was five-years-old when the U.S. government sent her to the Phoenix Indian School, more than 200 miles away from her Hopi family home. She was forbidden to speak her native language, her long hair was cut, and she was stripped of a traditional Hopi childhood.

At 18, she returned to the reservation, her American “assimilation” finished. Her own children would be sent to the school too, as were her grandchildren. Like generations of Native American families, they each experienced the same pattern of segregation — a legacy that experts say left a lingering impact on their education.

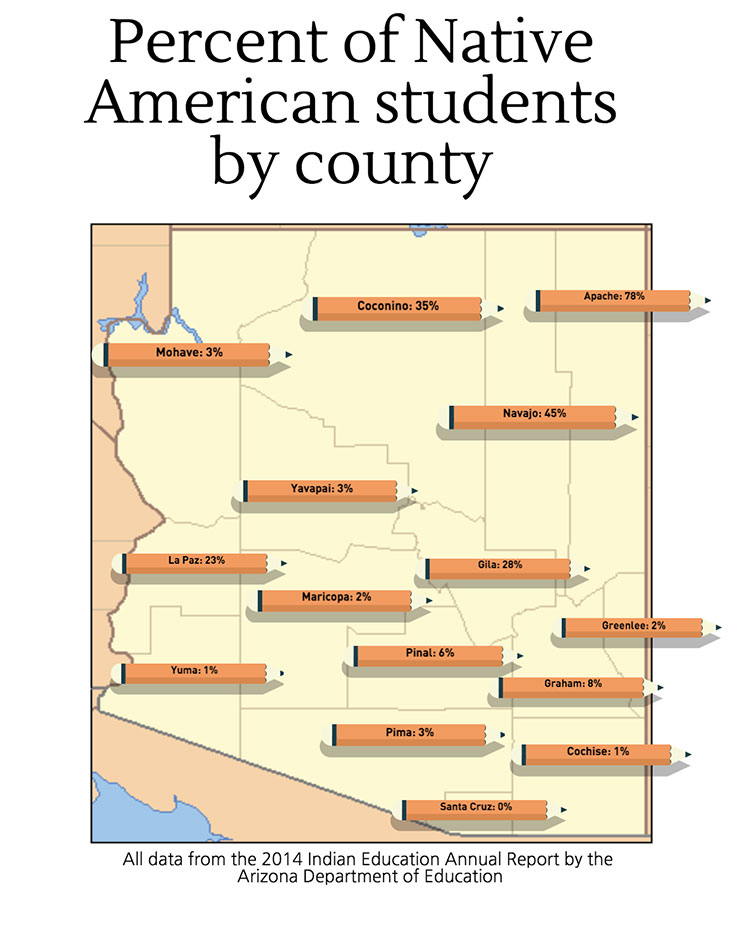

Today, Arizona has the third highest population of American Indians in the country and is home to 22 federally recognized tribes. And though it has the second largest Native American student population in the United States, children and teens are failing standardized tests and dropping out of school faster than any other group, according to the most recent 2014 Indian Education Annual Report done by the Arizona Department of Education.

“Look at the legacy of the boarding schools. Separation of child from family and community,” said Patty Talahongva, the granddaughter of Rosalie Lalo. “How would your family survive that? How do generations of that recover?

During the late 1800s and for decades later, the U.S. government opened boarding schools across the country with the purpose of assimilating Native American youth to American standards. Originally established to “civilize” American Indians into mainstream society, the “primary difference between Indian boarding schools and the mainstream education systems was segregation,” according to Phoenix’s Heard Museum.

Talahongva, who now works for a group called Native American Connections, witnessed the long-term impact of the Phoenix Indian School through her grandmother.

Talahongva attended the school after it was turned into a high school. She uses her position as community development manager to break down stereotypes associated with Native Americans by educating others about the history of tribal education and current problems facing tribes throughout the state.

“Typically, when I go out, I ask people to name five Native American leaders. Can you name five Native American leaders? And they can’t be dead,” she adds. “Most people can’t name five living Native American leaders.

The Phoenix Indian School, located at Central Avenue and Indian School Road, closed in 1990 after 99 years in operation. Students of high-school age have two options: Attend one of five Bureau of Indian Education high schools in the state or go to a public school closest to their home. Mostly because of location, 71 percent of students attend public schools near or on their reservations, according to the Indian Education Annual Report.

More than four decades ago, Jon Reyhner began his teaching career on the Navajo reservation. A history major, Reyhner taught sixth grade math because the school was so desperate for teachers. He now is a professor of multicultural studies at Northern Arizona University and cites less-than-adequate efforts to include history and culture into education as a main factor for students losing interest in school.

“Language loss is a major issue, and culture loss,” Reyhner said, adding that knowledge of culture and the practice of traditions and language help Native American students to better connect better with their heritage – and work harder toward an education.

Talahongva not only wants to raise awareness of current Native American issues, but also is working to remodel the old band building at the Phoenix Indian School, which is now the Steele Indian School Park in central Phoenix. The building will sit as a reminder of a time when culture was not allowed to be a part of Native American education.

It’s intended to be a center for celebrations of culture, a place for tribal leaders to gather and will include a memorial room dedicated to the history of the closed school.

“I only hope to grow, not only so people understand why Indian School Road is called Indian School Road, but what was the history of this place for 99 years, what was there before Arizona became a state,” Talahongva said.

The Native Youth Know program, a collaboration of local and national programs interested in American Indian welfare, is working to keep students engaged in education programs centered on culture and their tribes.

Projects in the Navajo Nation, for example, involve getting 5th and 6th graders to refurbish and manage a greenhouse and fundraising to give musical instruments to youth on the reservation. The Pascua Yaqui Tribe is teaching children about ancestral native diets, cultural resiliency and the history of their customs and traditions.

The Hopi tribe is having their youth develop a park to promote health and wellness in the tribe. Tribes also are trying to encourage students to leave reservations for higher education.

In 2000, the Hopi tribe established the Hopi Education Endowment Fund to help students go to college. The HEEF set aside $10 million for the fund and uses the earned income for an endowment to further education, on and off the reservation

Vernon Kahe, a resource development manager for the fund, said the money has been instrumental in bringing more Hopi teachers back to the reservation. Twenty years ago, he says, it was hard to spot Hopi teachers in Hopi schools.

Now, more than half of the teachers on the reservation are Hopi. Before the HEEF, Kahe said the tribe, was dependent on resources and income from coal mining to fund educational efforts.

“We are growing this [fund] for the future and the money that we do have, we’re stewards of it,” Kahe said. “We’re trying to develop a fund that lasts forever.”

Since the money was put in place, the Hopi Tribe Grants and Scholarship Program have provided over 4,500 grants to Hopi students across the nation at accredited universities, resulting in in 278 tribal members getting higher education degrees, according to their website.

The need for better education on reservations has gone beyond the local and state level. The Obama administration has been working to better conditions on a national scale.

The 2014 Native Youth Report by the Executive Office of the President specifically pointed to the low graduation rate of Native students nationally — 67 percent — which drops even lower in Bureau of Indian Education schools to 53 percent.

The report also found that by augmenting support of tribal cultures and traditions, students are more likely to connect with their community, want to improve it and continue with their education to reach those goals.

The state education department’s report notes that more educational programs now are available to Native American high school students and those entering college. Most community colleges and universities like Northern Arizona University, University of Arizona and Arizona State University have programs for new college students they hope to retain and graduate.

“A variety of programs are also offered for Native American students in the elementary and junior high school. For example, the Mesa Unified School District has a unique cultural and educational program that addresses students at each grade level,” the report says. “The purpose of this program is to increase the personal and academic self-efficacy of Native-American students while embracing and preserving Native-American culture.”

American Indian Student Support Services at Arizona State University has started a program that sends current students to the reservation to recruit for ASU. The Tribal Nations Tour brings one of the largest universities in the country to smaller reservation schools.

Bryan Brayboy, special advisor to ASU President Michael Crow and director of the Center for Indian Education, said administrators agree that not enough is being done even for ASU’s more than 2,600 Native American students.

“We have to create a climate and an environment at ASU where Native students feel welcomed,” Brayboy said, citing social structures such as friends, clubs, teacher relationships and dormitory life.

“The evidence is overwhelming that if you want Native students to do well, cohorts work and really good positive relationships work,” Brayboy said. “We’re not losing students because of some structural component that needs to be tweaked or changed.”

This spring, Gov. Doug Ducey passed an initiative expanding scholarship opportunities to students on reservations.

Arizona now has two tribal colleges to make it easier for native students to gain higher education. The Diné College and Tohono O’odham Community College have multiple campuses to give greater access to Arizona’s tribal members to seeking a higher education.

Talahongva said that through the scholarships and concerted efforts to return to tradition, schools are finding ways to reach children through their culture — and to educate them.

“We have our successes despite what happened to us, despite what happened to our families. And not just one generation or two, but many generations — the schools were open for 100 plus years, so that’s a huge impact,” she said.