More than 934,000 workers in Arizona, or about 45 percent of the state’s private-sector workforce, do not have access to paid sick leave, a new report says. Nationally, 39 percent of workers, or 43 million workers, lack the benefit. (Photo by Laura Mundee via flickr/Creative Commons)

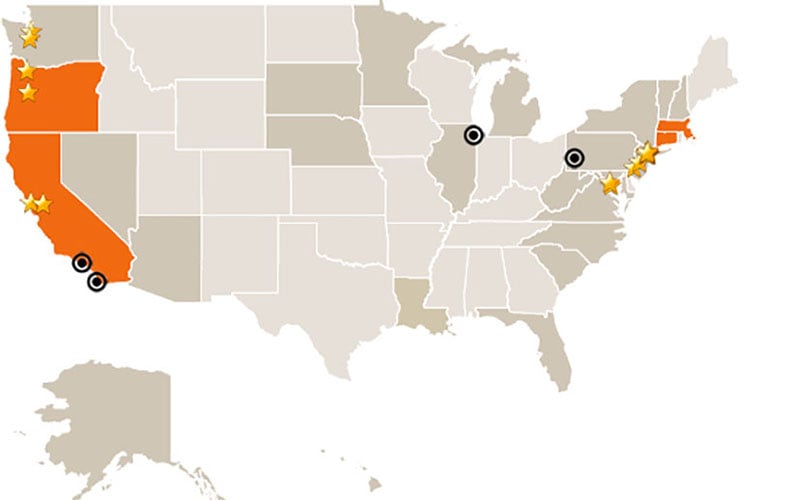

The states in orange and the starred cities have passed law giving workers the right to earn paid sick days. The circles and the states in gray – including Arizona – have been targeted for action on the issue by advocates. (Map courtesy the National Partnership for Women and Families)

WASHINGTON – Close to half of Arizona’s private-sector workers, more than 934,000 people, do not have access to paid sick leave, according to a report Wednesday by a group pushing for such laws.

But the National Partnership for Women and Families said Arizona is not alone: More than 43 million people, accounting for about 39 percent of private-sector workers in the country, currently don’t have the ability to earn paid sick leave, it said.

While the partnership plans to push for such laws – and said it has targeted Arizona for action – business representatives say that decisions on such benefits should be between employer and employee, and not imposed by the government.

Currently, four states and 20 local jurisdictions have enacted laws requiring paid sick leave for private-sector workers, and Democratic lawmakers launched efforts this week for similar measures in Congress.

“I believe that access to paid sick days is critical to the economic stability and security of all workers, regardless of their ZIP code,” said Sen. Patty Murray, D-Washington, who has introduced a sick-leave bill in the Senate.

Arizona does not require employers to provide sick leave benefits to their employees. About 45 percent of the state’s workers do not receive the benefit, the partnership said.

State Rep. Richard Andrade, D-Phoenix, sponsored a bill in this year’s legislative session that would have required Arizona employers to award a minimum of one hour of paid sick leave for every 30 hours and employee worked.

That bill died in committee, but Andrade said Wednesday that he plans to reintroduce it in the 2016 Legislature.

“We need people to start stepping up and telling their stories on how missing workdays without pay affects them,” Andrade said. “It will be an uphill battle, but I will keep fighting.”

Andrade said America needs to go back to protecting and taking care of working families, which is why he will again push for his legislation.

“There used to be employers who took care of their workers and realized the importance of providing paid sick time and we’ve gotten away from that in the aim for bigger profits,” Andrade said.

But business groups in Arizona said that such decisions should come from within the organization rather than by government mandate.

“Leave policies are best handled between employers and employees,” said Garrick Taylor, spokesman for the Arizona Chamber of Commerce and Industry.

He noted that there is no bipartisan support for Murray’s bill, or for a companion bill filed in the House by Rep. Rosa DeLauro, D-Connecticut.

But advocates are hopeful.

They said nearly 1 million Arizona children live in households where both parents work. Joshua Oehler, spokesman with the Children’s Action Alliance in Arizona, said not having paid sick days can cause financial burdens on families and higher medical bills for not getting the proper care early.

“It’s concerning that parents aren’t able to take sick days to care for their children,” Oehler said. “Most times parents send their sick kid to school and that gets other kids sick and it turns into a cycle and puts on extra stress on the child and family.”

Art Mendoza, president of the Service Employees International Union Arizona Local 48, said paid sick leave is an easy solution to what could be a complicated problem.

“It’s alarming that so many workers in Arizona don’t have paid sick time to be able to care for their families and for themselves,” Mendoza said. “It’s common sense that it doesn’t help anyone when folks are going to work sick especially for low-wage workers.”

But Taylor said the solution is not that simple, and it could have unintended consequences.

“Ultimately, increased mandates on employers make it more difficult to hire and expand their workforce, which in the end ends up hurting the very people that these policies are attempting to help,” he said.